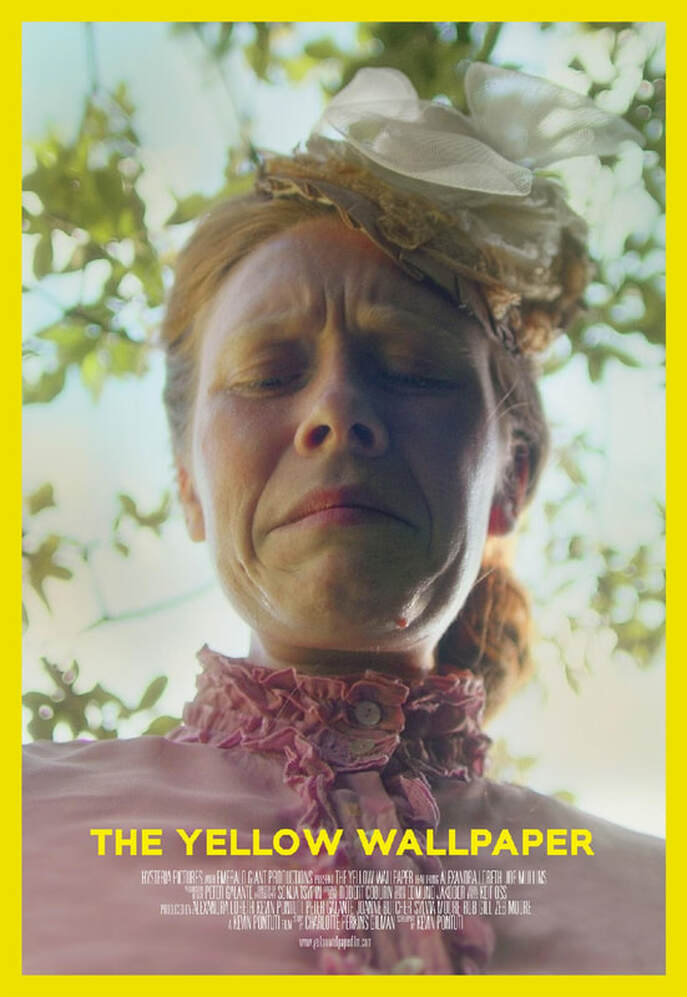

To call Charlotte Perkins Gilman a complex woman would be an understatement... ...An amalgam of progressive and incredibly regressive beliefs, she’s a difficult artist to make peace with. And yet, at least when it comes to her best-known short story, flying in the face of society’s comfortably held ideas is the point. While her most regressive beliefs are impossible to reconcile today, The Yellow Wallpaper did unquestionable good for shifting the way women’s mental health and the common practice of sending them out to the country to “rest” were understood. Fun fact: sending someone with a mental illness away to be virtually isolated, but at least out of society’s view, is…arguably the worst solution there is. But that’s the 1900s for you. Writer-director Kevin Pontuti’s adaptation of the story, which just had its World Premiere at Cinequest and is written with Alexandra Loreth, feels acutely aware of its subject matter and the subtle break of sanity that lies at the core of the text. Yellow Wallpaper is, first and foremost, a cautionary tale about the dangers of the fairly common practice of hiding away the things we do not understand. Just as they used to hide disabled children from view for fear of social shame, so too it seems best practice for treatment of mental illnesses like depression was to send them away to the country. The film and its base text both take this practice one step further by intertwining the two; Jane (Alexandra Loreth) stays locked away and does not interact with anyone outside the confines of her rental home. Crucially for the story’s reevaluation as a feminist text, Yellow Wallpaper puts the locking power in Jane’s hands. Nevertheless, we feel the air and the walls constrict around us as she descends further and further into her illness while everyone else tries their hardest to convince themselves that the “rest cure” is working and that Jane is getting better. Yellow Wallpaper is a bold, shocking, visually striking adaption of an already controversial text and it is admirable that no one involved wanted to shy away from the happenings beneath its surface. It seems impossible to come to this film unfamiliar with its source, and the filmmakers exploit this familiarity with visual cues to Jane’s mental health right from its opening shots. The carriage she and her husband arrive in is lined outside with yellow, the color we understand to be the very crux upon which Jane’s health dissolves. Her baby, whom she at one point unceremoniously and with little emotion on her face tosses out of the carriage window, is wrapped in a yellow patterned blanket. From that moment onward the stakes of Jane’s illness are clear—she likely has postpartum depression—and we know that the film is going to give her the space to articulate her condition without judgement. From us, anyway. While everyone in the house is good-naturedly and rightfully concerned, they also after a month or so begin to tell themselves she’s doing better, despite the fact that she more or less enters long stretches of being nonverbal and staring blankly at the wallpaper in their bedroom. Robert Coburn’s score is instrumental to building the slow-burn intensity of Jane’s mental state. It is minimalistic but effective, fostering a feeling of chaotic unease in viewers the deeper into the story we go. Often Wallpaper is little more than periods of silence broken up by concerned dialogues between Jane and her maids. When she is alone with her notebook and her thoughts and her stifling wallpaper is when the score becomes most discordant, particularly toward film’s end. The visuals also clue us in to her descent. One of the maids even goes so far as to note “that paper stains everything it touches” and remarks that it is becoming ever more impossible to keep Jane and her husband’s clothes free of yellowing patches. The push-pull relationship between the sickly colored bedroom and the bright, fresh air of the gardens is, of course, ultimately stifled by the dominating force of Jane’s depression. Lacking the energy even to leave the bed she foregoes her favored pastime and instead becomes consumed with the need to release the woman in the wallpaper and free herself from having to look at such an ominous pattern. So much so that Jane’s very skin becomes tinged with the color toward film’s end, when she is at her peak. Navigating a story like The Yellow Wallpaper is no easy feat. It requires a level of care and attention to detail unique to those things whose deeper meanings are held beneath the surface, and Pontuti and team are more than up to the task. It is by its very nature a slow-burn exploration of madness exacerbated by society’s standards, but there are many a line and an ending shot sure to linger in your mind long after the film ends, perhaps even tinting your very thoughts the color of Jane’s struggle. The Yellow Wallpaper makes it world premiere at Cinequest today from Hysteria Pictures. By Katelyn Nelson Celebrate Women in Horror Month with us by donating to Cinefemme at: Donate (cinefemme.net)

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed