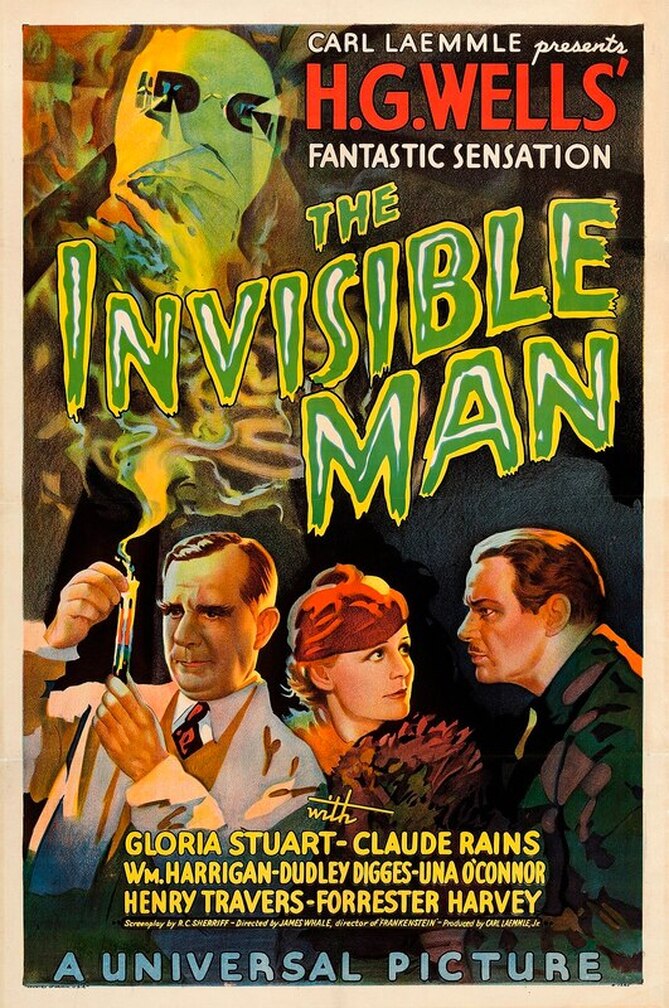

[Creepy Crypts] 'The Invisible Man' (1933) Introduced One of Universal's Most Enduring Monsters3/10/2021  The Invisible Man (1933) opens with a village inn receiving a strange visitor: Jack Griffin (Claude Rains), a scientist who keeps his face and experiments strictly under wraps... ...It turns out that Griffin has devised a formula that turned him invisible, and he has all manner of criminal plans that will benefit from this trait. The police struggle to apprehend a suspect they can’t even see, and when Griffin’s old colleague Kemp (William Harrigan) gets involved, the Invisible Man soon pressures him into serving as accomplice to his reign of terror… We live in a CGI-saturated era in which we have come to take special effects for granted as part of horror, fantasy, and SF cinema. There was a time, however, when a single special effect could be sufficient as a movie’s centrepiece, providing not just crowd-pleasing spectacle but the entire high concept of the film. Such is the case with The Invisible Man, in which the camera trickery used to turn the lead actor invisible was cutting edge at the time and still stands up well today. English stage actor Claude Rains makes his Hollywood debut as Griffin—although, given the character’s nature, this amounts in large part to a voiceover role. Rains’ vocal performance is deliciously ripe, mood-swinging from childish glee to brittle coldness, and truly bringing the unseen character to life (Boris Karloff was the first in line for the role, and truth be told, it’s hard to imagine Karloff’s sombre tones being quite as effective). One thing to bear in mind is that sound cinema was itself a relatively new development in 1933; the spectacle of Griffin’s disembodied shirt dancing around a room while emitting manic giggles was something that simply could not have been created only a few years previously. One reason for The Invisible Man’s success as a film is director James Whale’s sympathy for the original H. G. Wells novel, which was adapted for the screen by scriptwriter R. C. Sherriff. Wells’ flair for character-based whimsy (as represented by the various harassed locals) and morbid visions of science gone wrong mesh well with the camp horror of James Whale, who allows audiences to laugh and shudder in equal measure; one minute the Invisible Man is reciting nursery rhymes as he hands wads of money to bystanders, the next he’s engineering a train crash for his own homicidal pleasure. When it comes to adapting literature, the Universal horror canon is patchy. Dracula was based on a diluted stage version of Stoker’s novel rather than the book itself; Frankenstein used a (justifiably) large amount of creative license in translating the tricky novel to screen; and the studio’s Edgar Allan Poe adaptations are barely recognisable. The Invisible Man is a different matter, with much of Wells’ novel carried over in both spirit and letter. Granted, the film does make some significant departures from its source. One major character, who survives the end of Wells’ story, is given a dramatic death scene for the film. Another character, Griffin’s fiancée Flora (Gloria Stuart), is invented from the whole cloth and given the standard material for mad scientists’ fiancées—namely, pining over her lover’s increasing immersion in his dubious work. By and large, such changes do no harm to the story; the film’s one truly objectionable addition is the detail that Griffin’s invisibility drug also drives him insane, which muddies Wells’ psychological portrait (shades of the superfluous “criminal brain” in Universal’s Frankenstein). Out of all the strange beings dreamt up by H. G. Wells—the Martians, the Morlocks, the Selenites, the creations of Dr. Moreau—the Invisible Man is the only one who earned a place as a classic monster alongside the likes of Dracula and the werewolf, recognisable to countless horror enthusiasts from childhood onwards. This status can be chalked up to the 1933 film; the special effects may have won audiences over in 1933, but James Whale’s witty retelling of Wells’ novel is what makes it an enduring classic. By Doris V. Sutherland

1 Comment

vcnks for sharing the article, and more importantly, your personal experience mindfully using our emotions as data about our inner state and knosx sdvcvssd wing when it’s better to de-escalate by taking a time out are great tools. Appreciate you reading and sharing your story since I can certainly relate and I think others can to

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed