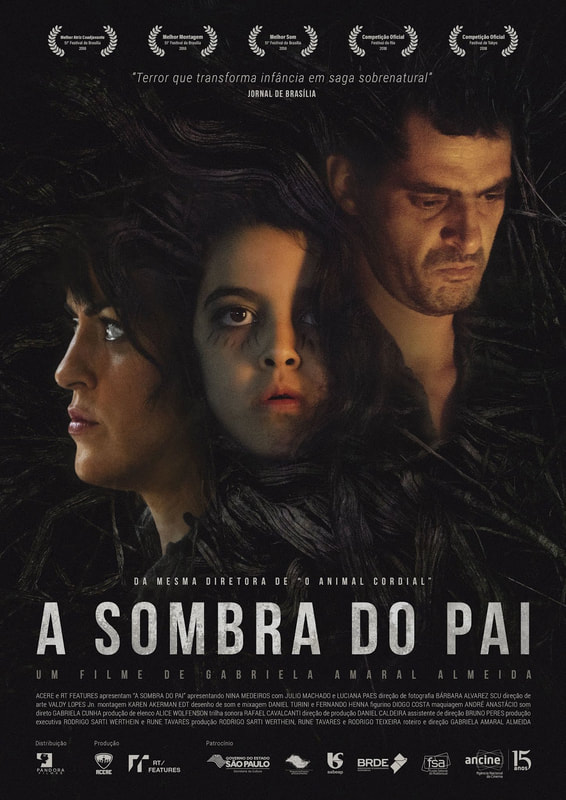

There’s all sorts of rules any horror fan worth their salt knows they should follow. Don’t go into the woods alone. Don’t mess with a Ouija board--it’s never just a game. If you’re under siege by a serial killer, never travel anywhere alone. Among these unshakable truths is the maxim that magic, especially black magic, will always come with a price... ... In writer-director Gabriela Amaral’s The Father’s Shadow, which recently played at the Final Girls Berlin Film Festival, this mantra is explored in a poignant, occasionally disordered tale of a fractured family dealing with a grievous loss and struggling to make order out of chaos while the young daughter, resentful and hurting, turns to the supernatural as means of processing her pain. Dalva (Nina Medeiros) wants nothing more than to have her mother, who died in an accident two years ago, returned to her. Her father Jorge (Julio Machado) has become aloof and detached, partly as a coping mechanism and partly thanks to his job on a Sao Paolo construction site riddled with safety hazards and noxious fumes. Nine-year old Dalva is primarily being looked after by her aunt Cristina (Luciana Paes), who is preoccupied with finding ways to get her boyfriend Elton (Rafael Raposo) to marry her, including a ritual involving the icon of St. Anthony and a drop of her own blood. Dalva is no stranger to the preternatural, as she appears to have a “gift” of her own, one that allows to ascertain that Cristina’s spell will not work and speak her own alternative into being. But this leads to a proposal, and subsequently Cristina moving out, and that means Dalva is effectively running the house as maid, chef, and finance manager since her inattentive father is too distracted to pay her any mind. The two make for a rather dour pair, but half-heartedly reassure each other that everything will be okay in the end. They could not be more wrong. The Father’s Shadow is a minimalist, artistic film in the vein of Tigers Are Not Afraid (2017), even down to the narrative device of having the fantastical elements of the story act as an extension of a young child’s psychological trauma in the face of the harsh realities of an unforgiving, adult world. Though the supernatural is an influence, at its core the film is a psychological family drama where tragedy and trauma lurk around every corner. It’s quite a bleak film in presentation and outlook, with both Dalva and Jorge gripped by an immense and pervasive sadness that seeps through the screen. Their grief is natural and understandable if difficult to watch. As the film progresses, their shared yet isolated pain manifests in different ways; Dalva sinks into old black-and-white horror films and escapist fantasies while her father becomes increasingly divorced from his daughter, his surroundings, and even himself. As both begin to separate from reality, the viewer is forced to question the true origin of the strange, sinister happenings that begin plaguing both Jorge and Dalva’s home and Jorge’s construction site. This uncertainty leads to some of the film’s strongest sequences, particularly at the construction site, where the shadowy, murky scares amidst the shorn infrastructure recall the oppressive atmosphere and the decrepit asylum from Session 9 (2001). Much like that film, Shadow presents the possibility that these disturbing events are all taking place in the characters’ minds, and that we may not be able to trust either Jorge or Dalva completely. Such ambiguity provides a lot of room for a filmmaker to play in, and it’s not all utilized effectively. Once it’s firmly established that Jorge is an emotionally distant father and Dalva is boiling over with resentment, the middle bit devotes itself entirely to reminding us of these facts and as such, drags along. Weird things are happening to father and daughter, but they never escalate or cohere into any narrative building blocks until well into the third act by which point there isn’t enough time left in the film to flesh things out in a satisfying manner. That being said, Shadow is a beautifully shot film thanks of course to Amaral and the camerawork of Barbara Alvarez. There’s some particularly excellent framing and movement when it comes to the playing of light in all its myriad forms, from flood lights to sunlight to stuttering votive candles. It’s also solidly acted, with Medeiros leading the film with a magnificent, heart-aching performance and Machado anchoring as the increasingly zombie-like Jorge, though the script doesn’t allow him to do much beyond act surly. Their performances blend well with the uncanny images present throughout and the ethereal score by composer Rafael Cavalcanti. There’s a sense of some larger social themes that Amaral and the film seem to want to take on, such as the concept of machismo in Brazilian culture, but the script is too loose to make any of these commentaries coalesce into anything digestible. With a tighter script and more fluid pacing these themes could have been explored with a bit more depth and nuance. That being said, The Father’s Shadow still tackles some heavy subject matter with a practiced hand and is bolstered by gorgeous cinematography, fully realized performances, and a haunting, otherworldly score. The amorphous social commentary doesn’t congeal enough to stick, but there remains plenty of solid components to leave the viewer feeling like they’ve grabbed on to something more than just shadow. By Craig Ranallo

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed