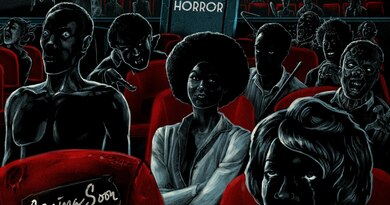

I’m a film lover. Since I was three and wore out a VHS copy of John Carpenter’s Christine, I’ve been fascinated with the art of moving pictures. I’m also a white male, which means that no matter how much I’ve studied and appreciated film in all my years, there are certain aspects of the art form which I may have realized but not fully understood. One of those is the inaccurate portrayal of blacks in cinema, particularly, horror. Thanks to Horror Noire, that mischaracterization will finally be shown to the world… …Written by Ashlee Blackwell and Danielle Burrows, based around the book Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to the Present by Robin R. Means Coleman, Horror Noire is a documentary directed by Xavier Burgin which takes a look at the history of black horror films and the role of black filmmakers/actors in the film genre, going all the way back to the creation of film itself. “We’ve always loved horror. It’s just that, unfortunately, horror hasn’t always loved us”. Horror Noire opens with this line, a line which immediately stunned me. I’ve always known of the tropes in horror like “the black person dies first”, but until now, it has never fully hit me how underappreciated and misrepresented the black community has been in horror. To think of that, what it must be like to love a genre of film which doesn’t love you back, it’s heartbreaking. That’s a feeling which I’ve never had to know, and the mere fact of that is why a film like Horror Noire is so important, because this has been an issue which has gone largely ignored outside the black community, and it’s time more people became aware of it. Horror Noire features a bevy of talented black filmmakers/actors & actresses to tell their stories of not just working in the film industry, but the way they viewed it growing up. You’ll hear stories from Rusty Cundieff (Tales from the Hood), Ernest Dickerson (Tales from the Crypt: Demon Knight), Keith David (The Thing), Jordan Peele (Get Out), Rachel True (The Craft), Tony Todd (Candyman), Ken Foree (Dawn of the Dead), William Crain (Blacula), and so many more. What’s great about this lineup, other than the fact that all of these filmmakers are talented artists in their craft, is that Horror Noire gives us a viewpoint on black horror from various generations. You’ll hear how Night of the Living Dead prompted Tony Todd to get into acting, (which is pretty inspiring, considering he went on to star in the remake). William Crain discusses making one of the first horror films which actually portrayed blacks as real people instead of stereotypes in Blacula, when Crain describes being one of the only black people on the crew in the 70s. And then there are the memories of Rachel True, who describes the frustration of having to be the black character that is constantly asking the white person if they’re okay, since so often in horror it’s always about the white person and never what the black character thinks or feels. These are fascinating, sad, and inspiring stories that are going to shock you, anger you, encourage you, and even make you tear up a little, which speaks to the power of Horror Noire. Some of these interviews are truly touching, like hearing Jordan Peele describe his worry over how the country would receive Get Out, a film which depicted the fears of black culture, and one of the few, if not the only, horror films where every white person is a villain. It’s an understandable fear, and thankfully seems silly looking now at how that film changed the conversation not just in horror, but in cinema entirely. And it makes sense, because as Horror Noire details, it really isn’t until recently that the horror genre has been kind to black culture. The film takes us all the way to the beginning, where the despicable film, Birth of a Nation, is described as a horror film. Back then, in 1915, the film, which depicts the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, was seen as some kind of great masterpiece by the whites. But for the black community, it was a horror film, depicting blacks as a menace. Horror Noire takes us deep into the history of horror films and how a film like Birth of a Nation carried over into the genre throughout the years. We’re taken through early decades when blacks were only cast as criminals and maids, into the atomic age of the 50s/60s, when horror delved more into scientific territory, leaving little room for black actors/actresses, since studios refused to cast them as scientists, through the Blaxploitation era, when blacks finally saw more representation, but again were treated as a new kind of stereotype in pimps and hookers. Horror Noire is not an easy film to digest, because as we go through all of these decades, it becomes more and more depressing and enraging to see the racism which existed in film so simply and eloquently displayed for all to see. Even though going through these decades will make you want to go back in time and punch studios in the face, Horror Noire isn’t just informative, it’s also a treasure trove for film connoisseurs looking to learn more about black horror films. Horror Noire introduces various films that I’m sure many viewers either haven’t heard of, or haven’t seen. Films like Son of Inagi, described as the “first black horror film”, or Ganja and Hess, which was kept hidden from audiences. By the time Horror Noire ends, you’ll have a long list of films that you’ll want to check out, or at the very least, revisit as soon as possible. Unlike most documentaries, Horror Noire isn’t split into obvious “segments”. The film doesn’t suddenly pause to let the audience know, okay, get ready, time to visit the 90s and the fact that black actors kept being forced to sacrifice themselves for some basic white girls. No. Instead, Horror Noire moves the conversation along like what it is, a conversation, transitioning from one topic to another without a block in the discussion. Some may find the transitions a bit sudden, but it works because it allows the audience to feel as if we’re sitting alongside the interviewees in this dark theater, which is much more engaging and personal, and the right way to discuss black history in horror film. My only complaint is that I wish there was more, because at a runtime of a little over 80 minutes, it feels like there is so much more to tell. What surprised me most about Horror Noire is that, in some ways, the film is less a celebration of black horror, and more of a statement on why it’s about time the world begins to recognize the importance of inclusion in cinema, and the eradication of false stereotypes. But don’t take that the wrong way. Horror Noire sings the praises of accomplishments in black horror cinema loudly enough to bring the roof down in the theater. But the whole time that the filmmakers are having this intimate conversation with the viewer, they are emphasizing the need for change, coming back full circle to Get Out and how this could finally be the film that broke the racist’s back, leaving us with the hope that the exclusion and misrepresentation of black culture in horror cinema is dead, or at least taking its dying breath. To my knowledge, there isn’t another film like Horror Noire out there for genre fans. Horror Noire is a crucial film for this generation, one which speaks to the importance of film, and the impact that it can have on a culture. Some, especially white males, have taken our representation on screen for granted. But film is for everyone, and Horror Noire is eye-opening for those that have never had to look for representation in film. It’s astounding yet not all that surprising, unfortunately, that a film like Horror Noire has taken this long to come into existence, but I’m so glad it has, and there is no doubt in my mind that the horror community will feel the same way. Horror Noire releases on Shudder on February 7th. By Matt Konopka

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed