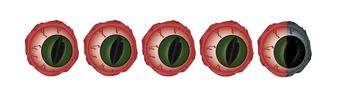

A couple months ago, Hulu and Blumhouse premiered their joint effort, Into the Dark, a horror anthology series which releases one feature-length episode every month, revolving around some sort of holiday related to that month, beginning with The Body in October. While both The Body and Flesh and Blood were decent horror fare to one degree or another, Into the Dark may have its first genuinely classic episode in Pooka… …Directed by Nacho Vigalondo (Colossal) and from a script by Gerald Olson (Back to School Mom), Pooka takes its inspiration from, what else, Christmas, and tells the story of Wilson (Nyasha Hatendi), a struggling actor desperate for work. He is offered a job by a sleazy marketing agent (Jon Daly), to play the role of this year’s hot holiday toy, Pooka! In other words, Wilson is given a demeaning job as a guy in a suit. But what Wilson is at first opposed to, he soon cannot live without, and finds himself slowly being taken over by Pooka. Is he losing his mind, or is there legitimately something evil about the suit itself? Pooka works on so many levels for me, that it’s difficult to know where to begin. The film opens with an ominous tone involving some kind of crime scene, flashing police lights and all, and a Pooka doll lying on the side of the road, gurgling out the eerie phrase, “look at all the pretty lights”. We’re then transported back in time, or so we think, where we meet Wilson, getting ready to head out on an audition. Vigalondo/Olson are smart to begin the film this way, because it establishes Wilson as an unreliable narrator. Knowing the basic plot, and given the sense that Wilson’s actions have led to something awful, we as the audience know that we cannot trust anything which Wilson experiences. And as the film progresses, this becomes more and more true the further and further Wilson slips into panicked confusion and potential insanity. It’s a brilliant ploy and one of the most engaging types of storytelling, because it leaves the audience completely vulnerable. In not knowing whether or not we can trust Wilson’s viewpoint, we are left on the edges of our seats in wondering what’s real and what isn’t, leaving us open to multiple shocks and surprises, which Pooka delivers on again and again and again. Much of the film’s brilliance is achieved through a superb grouping of talent all around, in particular, the editing. When it comes to films like Pooka, well-timed, detailed editing is a must, because the right kind of editing can create that jumbled sense of time and space that distorts what the audience perceives as reality into something which is foreign and mysterious. For example, Wilson may see something and go running after it, and then suddenly, we’re in a completely different moment with Wilson entering a party, cut together in such a way where instead of the viewer feeling as we have begun a new scene, it feels more like a continuation of the previous scene, even though they are unrelated. Did we just experience a time jump? Is this a memory? Is this all in Wilson’s imagination? We don’t know, and it causes a disorienting effect on the viewer which speaks to the power of the manipulation which is going on in Pooka. Amongst filmmakers, it is believed that there are three different storytellers in filmmaking: the writer, the director, and the editor. Each takes the idea and tells their version of the story. Imagine if Memento was told in chronological order (that cut exists, by the way, and is not nearly as good). Without the right editing choices, a provocative narrative can become streamlined and basic. The same goes for Pooka, because without the proper editor, Pooka could just go completely by the book with a straight forward narrative that wouldn’t be nearly as effective as what we are given. Thankfully, that’s not the case. Of course, writing and character development also play an important role in the deception of Pooka, as does the performance from Hatendi. When we first meet Wilson, he is an extremely sympathetic character. Any artist who has lived any sort of “starving artist” period will relate to Wilson’s struggle and his firm belief that he is an actor, and wants nothing more than to prove that to the world. So, when Wilson is forced into an awkward audition that involves being made to raise his arms and spin around like a plane to the gleeful delight of Daly’s character, the audience is given a glimpse into the absurdity of the audition process and the way in which talent is often abused in this cold, Christmas cheerless industry. We’re already rooting for Wilson, and we want him to get the part, but damnit, why must it be at the expense of his dignity, man? Hatendi perfectly resembles the fragility of Wilson, which makes it all the more heartbreaking as we watch Wilson’s life begin to crumble, just as he is beginning to form a family with new girlfriend Melanie and her son, Tye (Jonny Berryman). The entire cast delivers an exceptional performance which will tug at your heart strings, though Hatendi does admittedly struggle with his character’s more vicious moments, having a much easier time with getting us to sympathize for him than fear him. As for Pooka himself, he is easily the coolest, creepiest toy ever unleashed on the clawing hands of drooling children. As a toy which has a permanent “naughty or nice” setting, which is unpredictably controlled by Pooka’s AI chip, Pooka records random phrases said around it and, when it feels like it, repeats those phrases in either a “nice” voice or a “naughty” voice. Predictably, the “naughty” voice is fucking terrifying. So why would parents want to buy this thing for their kids? Because kids be crazy, and parents be desperately wanting to shut their kids up and just give them the damn toy. Some of you may not remember a time when toys like Furbies or that obnoxious red asshole, Tickle Me Elmo, were such hot commodities, that parents were trampling each other in toy stores just to get their hands on one. With the advent of the internet, shopping crazes like this have become less focused on one particular item, but the thematic elements of Christmas are still painfully present: either get your family what they want for Christmas, or die. Figuratively speaking, of course. Pooka in many ways reflects that same idea. As his relationship with Melanie and Tye grows deeper, so too does his need to keep them happy. Christmas is a stressful time, and Wilson’s character is the epitome of that stress, as a man who is fighting to give his family everything they want, even if it means losing his damn mind in the process. And in enters Pooka, the darker side of Wilson’s personality which is growing stronger as the stress builds. It’s arguable that Pooka is a commentary on the way in which actors become the role which they are playing. We’ve often seen the Jekyll/Hyde dual-personality dynamic portrayed in genre film, but there are very few which have done it as provocatively as Pooka. Vigalondo finds various ways to explore this idea. When Wilson first puts on the monstrous Pooka suit (props to costume designer Alexis Scott for her outrageous design), he finds he can’t breathe in it and has a panic attack. Later, Wilson has a hard time breathing when he’s NOT in the suit. And then there’s the fact that Pooka is filled with moments in which Wilson is wearing pieces of the costume casually. We’ll see him wearing either just the body, or the head, as if he is going through some sort of werewolf transformation or body horror deal in which he is becoming a monster. You could also say that, at a certain point, it seems as if Wilson is so overtaken with wanting the acceptance of Melanie’s son, Tye, that he even wants to become Pooka because that’s something which Tye loves, and Wilson is allowing himself to be overtaken by the suit so that Tye will love him equally or, better yet, even more. If you haven’t figured it out already, Pooka is an extraordinary mind-fuck that cares so little whether you get it or not, that it doesn’t even leave you money for the Lyft ride home after its boned your brain so hard it’s leaking out of your ears. Vigalondo is a unique storyteller, as is demonstrated by his past work, and there is no shortage of “what the fuck is going on” imagery in this film. The lighting is at times unnatural, like a comic book, with a single room burning red in an apartment building otherwise lit naturally. Or how about demonic images of Pooka with fire burning in his hellish eyes while he roars at us like John Candy cackling at Steve Martin in Planes, Trains and Automobiles during the infamous car crash scene. Pooka is so strange, so unnerving, that if you imagine what The Shining would have been like had it been directed by David Lynch, you’ll start to get an idea of what’s in store with Pooka. Throw in a few elements from Charles Dickens A Christmas Carol, and Pooka establishes itself as a horrific Christmas tale that should eventually become preferred viewing every December. Pooka is truly an inspired work, and is hands down an instant Christmas horror classic. Into the Dark: Pooka is now streaming on Hulu. By Matt Konopka

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed