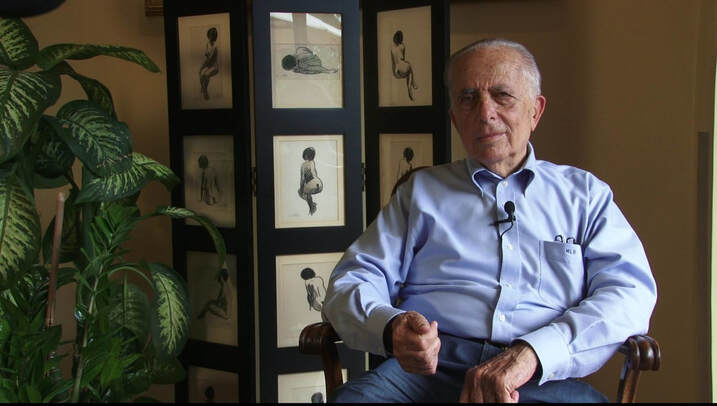

Most Americans will be able to cite why the 1970’s were a turbulent time of change for the United States. Vietnam. Watergate. Increasing social change as a result of the Civil Rights and sexual liberation movements of the 1960’s. What fewer people may know, however, is just how equally tumultuous events were across the Atlantic in many European nations, particularly Italy. While the 70’s were a peak decade for Italian cinema, they were also the apex for domestic terrorism, state corruption, and rampant violence… …Having just played at the Salem Horror Fest, the new documentary That’s La Morte: Italian Cult Cinema and the Years of Lead, directed by Xavier Mendik, examines how the films of that era--in particular the western, horror, cop, and sex comedy genres--reflect the political and historical developments of the time. Through interviews with directors, producers, screenwriters, actors, and composers, That’s La Morte sheds light on just what it meant to live during the Age of Bullets, and how film preserves that narrative in a way no textbook ever could. The documentary begins its exploration of Italian film in the 1970’s with a look at the spaghetti western films made prominent by producer Luciano Martino through his company Dania Studios. At first, Martino had his directors simply copy the successful films coming out of Hollywood at the time, such as Ben-Hur (1959). In some cases, Italian filmmakers were even using the same stock footage from American historical epics and espionage thrillers to make films like Giants of Rome (1964) and Secret Agent Fireball (1965). Studios would invent American names for their cast and crew and slap lurid, nonsensical titles onto their films in order to pull in audiences. But what began as imitation films quickly became a tool by which Italian filmmakers learned their craft on the job. Soon, they were making films on par with Hollywood’s greatest, and given how cheap it was to shoot a western, studios could produce three or four films at a time, leading to massive output and huge returns. But the western began to wane in the public’s eye as the 60’s wore on, and after a brief respite with the comedy western, it fizzled by the turn of the decade; then, with the debut of The Case of the Scorpion’s Tail in 1971, horror became king of Italian cinema, and more specifically, the giallo. From the Italian word for “yellow,” after the colored-coded paperbacks of the day (yellow signified crime fiction), giallos--or gialli--were psychological thriller/horror films often featuring the serial murder of young women and involved a sense of mystery. Dario Argento’s The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970) is regarded as having kickstarted the sub-genre, but many more would soon follow. As the scholars and filmmakers featured in the documentary describe it, the gialli were seen as a reflection of shifting sexual thinking. Regarded as an exploration of S/M play, these films were a way for audiences to indulge in the taboo without compromising their sense of propriety or community. After all, as Italian culture scholar Ruth Glynn points out, the victims were always foreign and the action always took place somewhere abroad. To have set such stories in Italy, she posits, would have been to suggest that Italy was not good-natured at its core, and that would have been unacceptable. Yet as the 70’s wore on, there was a dramatic shift in Italian culture. The traditional Mediterranean family structure was transitioning into a more modern unit. Women began to enter the workplace and explore female sexuality, threatening a long entrenched patriarchy bearing anxiety about female empowerment. A drastic and violent era in politics exploded out onto the streets and soon shootouts, kidnappings, bombings, and kneecappings became the norm for the average Italian citizen. Suspicion, fear, and paranoia were rampant. These days would later be christened the Years of Lead and it is here that the film really hits its stride. All of the directors and actors and screenwriters interviewed have personal ties and recollections to this time when domestic terrorism reigned supreme and it became unclear which side was worse and if the state could truly be trusted. They cite real-world examples of how stories in the newspaper directly influenced the stories they made for the screen, such as the kidnapping of politician Aldo Moro and its relation to the film The Violent Professionals (1973), or the infamous Fenaroli murder and its effect on gialli like All the Colors of the Dark (1972). While this is certainly the most fascinating part of the documentary, it should also be noted that it is here where the coverage moves from a dissemination of the gialli to an exploration of the Italian cop films and the sex comedy, which supplanted the gialli as Italian cinema’s most marketable genres as the 70’s faded into the 80’s and the Years of Lead gave way to a resurgence of the personal in Italian culture and a desire to retreat into the warm embrace of nostalgia. Examining how the sex comedy commercialized and comodified female sexuality while featuring very little actual sexual activity is interesting in its own right, but those viewers looking for further insight into the making and significance of gialli will have to look elsewhere. That’s La Morte is an examination of all the distinct types of cult cinema in Italy during the 1970’s, not just horror, and is a fascinating treat for cinephiles and horror hounds alike; though fright freaks beware that much more is covered than just our beloved terror genre. All of the featured directors, producers, stars, and writers are insightful and passionate about their work. There’s a sense of giddiness in getting to see Argento, Deodato, and Lenzi discussing their films alongside Edwige Fenech and George Hilton, and history buffs will love learning about a shadowy part of Italy’s history. Most will probably want more, and that may be the documentary’s one downfall. It’s only about 80 minutes, and with so many talking heads to spend time with, certain threads get cut off while we’d still like to unravel them, but overall the narrative gets told, and told with grace. Like a good Italian wine, That’s La Morte is meant to be sipped, doesn’t overstay its welcome, and is easy to savor. By Craig Ranallo

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed