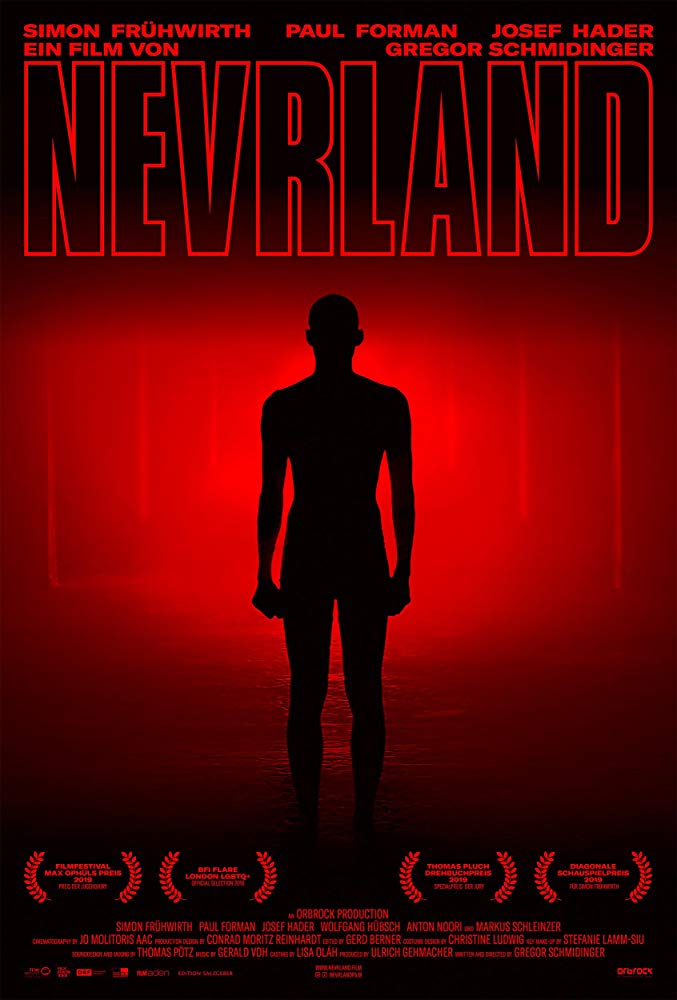

“I say unto you: one must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star. I say unto you: you still have chaos in yourselves,” a quote from perennial art school favorite and famed German philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche, begins our tumble down the rabbit hole in Gregor Schmidinger’s Nevrland, which played this past weekend at the Salem Horror Fest… ...Nevrland follows Jakob (Simon Früwirth), a 17 year-old high school graduate on what amounts to a coming of age and sexual awakening. A seemingly sensitive boy with a penchant for fantasy, Jakob lives a muted life amidst his dwindling family in their oppressively beige flat. His grandfather (Wolfgang Hübsch) suffers from the aftermath of what is likely a stroke that has rendered him nearly speechless, while his father (Josef Hader) adopts a similar if unearned stoicism. After learning that his father has arranged a job for him at the slaughterhouse where he works, Jakob retreats to his room where he explores his sexuality on sites like Cocktube and Cambuddies. Despite the somber silence of his home life aside from the chatter of the television, I spent most of the scenes in the home filled with unease that his father would discover his budding homosexual inclination and resort to violence. It seems so common a device in domestic explorations of young queerness. I’m almost refreshed by the lack of aggression toward queerness in Nevrland. Forgoing the hardcore bang and slap of oiled flesh, Jakob ventures onto Cambuddies for something more intimate, more personal. Enter Kristjan (Paul Forman), a fit, tattooed 26 year-old foreigner living in Vienna. The two hit it off flirting, Jakob disrobing and revealing a large red birthmark on his chest before spotty wi-fi disconnects them and he’s left with only his impending day at the slaughterhouse to accompany him to bed. Jakob seeks solitude in his fantasies amidst the screaming of pigs and the sawing of flesh at his first day on the job. His distaste for the work and discomfort with his body in the presence of his new co-workers become quickly apparent in a post-work locker room scene where he opts not to undress and shower. It leaves the audience to wonder if it’s his birthmark or his sexuality he fears exposing. Jakob embarks home, strangely alone given that he works with his father. In the train station Jakob unknowingly passes what appears to be an underwear advertisement featuring Kristjan as its model, the word ‘psychopomp’ emblazoned vertically in large letters beside him. Psychopomps are traditionally creatures, beings, or spirits tasked in escorting souls from life unto death. An interesting yet nearly missable touch from Schmidinger. On the train, Jakob succumbs to what will prove to be the first of many mental disturbances as the hardcore images from Cocktube are superimposed over the charnel house of pig corpses and the screams of swine. He alights the train only to see Kristjan sitting beside one of the passing windows smiling at him. Jakob and Kristjan’s paths intersect after Jakob suffers a sudden personal loss. And Kristjan lives up the ethereal nature of the psychopomp, asking probing questions about life, death, and art. At any given point there is an underlying uncertainty not only as to what is real and what is a dream, but also if Kristjan is real himself. We never really see him interact with anyone besides Jakob. We’re also left wondering if Kristjan is ushering him toward sexual awakening or death. At one point Jakob queries Kristjan as to whether or not he’s wondered what it would feel like to die, in the moment. Kristjan offers him the opportunity to find out, a line delivered in flat affect, almost purposefully without menace, left to linger in discomfort before he offers Jakob the chance to try DMT. Explaining that it’s a chemical compound released by humans upon birth, death, and dreaming. Jakob accepts, but it’s an event that seems almost too late in the game, a moment of incitement better suited for the first third of the film, rather than the last. It was in the moment that Jakob accepted the DMT that it coalesced for me exactly what this film was trying to do. It’s Schmidinger doing his best Gaspar Noé emulation in an LGBT context. While certain stylistic flair is cribbed to marvelous effect (pulsing credits, creative use of framing, color and lighting effects, hallucinatory concepts, and eternal recurrence) it fails to capture the heart of the raw and frenetic energy that invigorates Noé’s films. Invariably, Nietzsche’s philosophical concepts can be mined out of nearly each scene and from the film as a whole. The broadest among them being the concept of the Apollonian and Dionysian. The Apollonian seen in Jakob’s dreaming or hallucinatory states, and the Dionysian in his use of drugs and eventual submission to his sexual desires, burning away personal and emotional boundaries. Schmidinger is even so bold as to use a statue of Dionysus in a museum scene in the latter half of the film, making no mystery of his intentions and allusions. Still, for much of the film I felt Jakob in the opening scene, running through the woods and free falling off the cliff, was a stand-in for the film’s plot with the audience as the camera, hopelessly trying to catch up and see what’s coming or glean some meaning from what we’re seeing. But perhaps Kristjan best sums it up as he does for Jakob after he admits he doesn’t understand what most of the art in the museum means, “ It’s not so much about understanding it, it’s more about experiencing it.” Very art school indeed. By Paul Bauer

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed