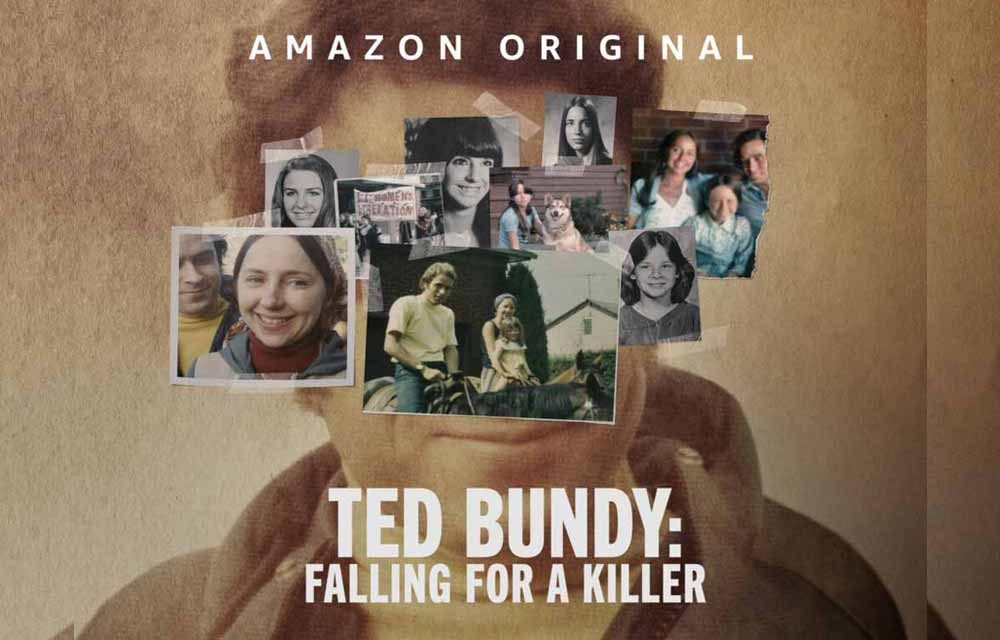

“What can I see in this man that would alert me? Nothing. I couldn’t recognize danger...” ...These are the words of Polly Nelson, Ted Bundy’s lawyer while he was on death row, upon first meeting him and trying to feel out the situation. There were, after all, plenty of people who believed his continuous claims of innocence, and, as she says, “it’s every lawyer’s dream to defend somebody on death row.” It was her first big case. It sounds like madness to us now, not being able to tell that Bundy was so horrible right from the start. He’s one of the most notorious and vile serial killers out there and, as the past year can attest on one streaming platform alone, one of the most (in)famous. In 2019 there were back to back releases of movies—both documentary and fictional—about his life and crimes. The Ted Bundy Tapes and Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil, and Vile were released within two days of each other on Netflix, and for a while they were all anyone across social media could talk about. He isn’t the only one to receive such heightened levels of attention by any means, but he is one of the few to spark a rather problematic conversation about his attractiveness nearly every time some new spotlight hits him. Probably he would have loved the attention we give him now. He craved people’s attention and affection and would do anything and be any way to get it. But this isn’t about him. At least, I’m going to try and make it as little about him directly as possible. The truth is he’s the least important figure in the story I want to talk about, even though he casts an impossibly long shadow over it all. In our desire to know more about serial killers and the how and/or why of their crimes, we sometimes forget the people who actually matter—the victims and survivors. Bundy is but one of many boogeymen made all too real, but how many women’s names do you know who survived him? Or who didn’t? Amazon Prime’s newest documentary series, Falling for a Killer, is the first in-depth look I’ve ever seen almost exclusively from the perspective of people who survived him. Told primarily by his longtime girlfriend, Elizabeth Kendall and her daughter Molly, as well as by several of the women who survived attempts on their lives, it reframes the story we all love to recycle into something that forces us to confront the women left in the shadows of the usual telling. More than that, though, it forces a truth on us we don’t like to confront even now—sometimes we don’t see the danger that’s in front of us not because it isn’t there, but because we don’t want to. If we face it, everything we thought we knew becomes a lie. People always question why those in abusive and manipulative relationships stay so long with someone bad for them. The truth is, the danger is rarely so immediately apparent, and sometimes doesn’t surface for a long time. Long enough that you never know the complexity of the situation until you’re in one. It is also true that no two stories are exactly the same. There is no way to reduce the question down to a single answer. Liz and Molly Kendall know that as well as anyone, and their telling of this story is a step toward closure and release. One of the hardest things to understand about being in an abusive relationship is what it can do to your mind. How it feels to have one version of someone in your head—the version they presented you with initially—forever clashing against the version of themselves that turned out to be the truth. How it feels to love them even while doubting them. What it does to you mentally and emotionally to begin to question everything you thought you knew about someone and who they were and who you were to them. The turning of your thoughts against yourself is so soft and slow you hardly realize it’s happening until the damage is done. Far before she ever began to worry and wonder about his actions, Liz Kendall started viewing herself as less than her boyfriend who put forth such a clean image. She changed the way she dressed, thought about the kinds of choices he would want her and her daughter to make, and made them in order to elevate herself to his level. Even when his level started to sink, she didn’t see it as his fault, but rather as potentially the result of something she did or said. When his moods shifted abruptly into silence and brooding, she worried she made him do it. She loved him so much she even twisted the narrative when details of his crimes started being released. It was a bronze car, not a dark brown one like Ted’s, so it couldn’t be her Ted. And yet, she called the police twice. Once when the suspect sketch got released and once more, and both times she was told they had already looked at him and he “wasn’t a good candidate”. She loved him and feared him. He made her feel happy, but also progressively more afraid. They could switch back to their normal conversation patterns in an instant, even as he sat in prison. But she wasn’t the only one to feel such an internal battle. Molly Kendall was little more than a toddler when she met her mom’s new boyfriend, and she was taken with him instantly. He gave her the kind of attention children crave; completely focused and invested almost right from the start. She trusted him completely. So she, too, rationalized situations he put her in as little more than getting overly excited and invested in a game. She was a child, and she wanted to be protected by this man who showed himself to be safe right up until the moment he wasn’t. She watched her mother fall in and out of a poison cycle with this man who was looking for nothing more than control over someone he knew he had a hold on. All it took was a few pretty words and Liz would fall back in with him, against her gut feelings, because she wanted to believe he was good—because she wanted to believe she was right. “You don’t go with someone for four years and not know what they’re about,” Liz says in Falling. She believed he was good, only struggling against something inside himself, and she wanted to help him. His other survivors faced a similar battle with the same circumstances on a smaller, although somewhat more acute scale. He never went back for anyone he attacked that got away, but they made choices informed by their beliefs in the basic goodness and safety of the world, and by what they had been taught: women should be kind and submissive in all situations—even rape—lest they face even more dire consequences. They followed a man who pretended either to be injured or an authority figure seeking help, simply because he asked for help and they had grown up under the belief that women should always be helpful. They got away because, in one way or another, they fought back. Against him and against the ideas that had been forced on them that were starting to crack in the ‘70s. He preyed on the knowledge they would act on an impulse of trust and kindness, but never seemed to consider the wave of fierce independence beginning to make its way to the forefront that told them they didn’t need to submit. If they sensed danger, they had every right and every ability to get away from it. Because sometimes, people aren’t good. Sometimes they’re predators, and people like Liz and Molly Kendall, Lynda Healy, Georgann Hawkins, and Carol DaRonch were the prey. They and countless other women were victims not just of one man, but of a system that wanted to brush their claims and their fears under the rug. When Carol DaRonch came forward in court about her attack, she was asked by several people if she was “sure she had the right man” because he “didn’t look the type”. Whatever “the type” is—some physical manifestation of evil we think we can sense immediately when we look at someone, some window into the inner Hyde to everyone’s projected Jekyll—no one wants to believe even today that sometimes the most insidious people are the ones who look as put together as you wish you could be. We see it all the time. Every time a young man gets off a rape charge because it would “ruin his future”, what is being said is “are you sure you have the right guy? He doesn’t look the type. What if you’re wrong?” and what gets left behind is the victim whose life is already ruined. There are parts of themselves they can never get back, things they will have to contend with internally for the rest of their lives. Because no one wants to hear and acknowledge the truth. Not then, and not really now. When Lynda Healy went missing, Falling shows us, some of the first observations made by the cops who were looking for her were “maybe she ran off with a boyfriend” and “maybe she’s off having an abortion”. When the number of missing girls started increasing, none of the police departments were talking to each other to figure out if any of the cases were connected, simply too busy trying to be the one to solve it. As a result, more women lost their lives. The trouble is, he knew how they worked and where the weaknesses were. Watching Liz and Molly Kendall and all the other women who had never gone directly on record in quite this way before coming forward to tell their stories was a bit of a gut-wrenching experience for me as someone who has been in manipulative relationships before. I’ve had those thoughts of guilt and shame, and in some ways, I’m still working through some of them. I recognized some of my battle in theirs and cheered with them when the spell was finally broken between Liz and Ted. It takes an immense amount of willpower to let go not just of the version of someone you thought you knew, but of the truth of who they truly are, and it is a years-long mental battle filled with complex emotional struggle. There may remain a part of you that loves that person, but the important thing is remembering that they were wrong completely independently of you. Their actions and mistakes are not yours to apologize for. The only person you have to forgive is yourself. Watching these women apologize for the actions of a man who did nothing but take advantage of them or lie to their faces or otherwise turn out to be entirely different than they ever knew was heartbreaking, but it is as true to life as any of the rest of it. Women who have been in situations where they’ve gotten taken advantage of feel compelled to apologize and rationalize because it was how they got by for so long. Unlearning the compulsion is a constant process. Overcoming traumatic experiences of any kind is an endless fight, but it is one worth fighting, and one we can win. We don’t even have to do it alone. There are so many of us out there; it’s part of why Liz Kendall decided to break her silence following the release of the two movies released in 2019. Her voice deserves to be heard with as much attention and voracity as he ever got. By Katelyn Nelson Like Katelyn's writing? Leave her a tip here through Ko-fi!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed