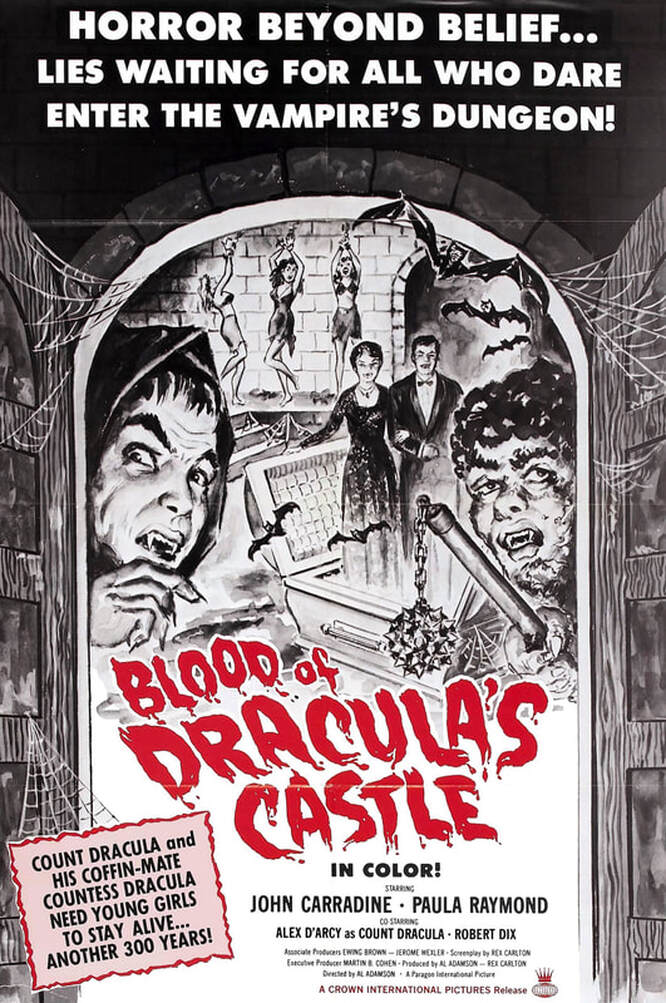

Welcome to a weekly series in which Doris V. Sutherland takes readers on a trip through the history of werewolf cinema... ...Blood of Dracula’s Castle (1969) opens with carefree young fun-lover Glen (Gene O’Shane) inheriting a castle from his uncle and heading there in the hopes of settling down with his fiancée Liz (Barbara Bishop). But the castle is already inhabited—by Count Dracula (Alexander D’Arcy) and his extended family. Once they arrive at the castle the young couple meet not only the Count but also his wife (Paula Raymond), butler George (John Carradine), brutish caretaker Mango (Ray Young) and even a resident werewolf, Johnny (Robert Dix). This is an early film by schlock-merchant Al Adamson, who teamed up with writer-producer Rex Carlton to cobble together a transparent imitation of The Old Dark House updated for an era in which campy monster-mashes were in vogue. The result, it has to be said, is a mess, its main failing being that Adamson shows no understanding of what made his source material work in the first place. The Old Dark House subgenre thrives on claustrophobia, with various mismatched characters crammed into a single building as tension mounts. Blood of Dracula’s Castle botches this by spending too much time outside the titular location. The opening scene—set at an aquarium—seems more interested in giving us extreme close-ups of walruses than in establishing mood; and even before the protagonists arrive at the castle, we have been given a long-winded sequence of the werewolf scampering though the countryside killing people. The film makes an effort to put unusual twists on the classic monsters, sometimes hitting on a good concept, other times falling flat. Count Dracula is reimagined as an old money New Englander who enjoys his cobwebbed surroundings while also appreciating the conveniences that come with modern life—such as the new-fangled methods of blood extraction that are on offer. It’s a nice idea, but one that never reaches its full potential, in part due to Alexander D’Arcy’s portrayal of the Count as an insipid Gomez Addams cosplay. Paula Raymond’s turn as Mrs. Dracula, on the other hand, is something of a delight and easily the strongest part of the film: the castle matriarch is cast as a snooty hypocrite who clutches her pearls at the thought of neck-biting but has no scruples about letting her servants do the dirty work. The werewolf character also has a twist. Rather than the angst-ridden figure of cinematic tradition, Johnny delights in homicide even before his fur grows. After escaping from an asylum, Johnny casually drowns a bikini-clad bystander, shoots a hitchhiker in the face to steal his clothes, and pushes a hijacked car over a cliff with the original owner trapped inside—all while in human form. Presumably influenced by Psycho and other psychologically-oriented horror films of the sixties, Blood of Dracula’s Castle makes an effort to get into Johnny’s head and explore what drives him to kill. This is an unusual take on lycanthropy, and it’s easy to see why: if a werewolf behaves the same way in both his human and wolf forms, there’s no point in him being a werewolf. One ludicrous scene has Johnny smugly proclaim that he feels no need to fight against his impulses to kill—except for when the moon is full, at which point he feels an uncontrollable impulse to kill. The film shows no awareness that this is blatantly self-contradictory. Having cribbed from the vampire, werewolf, Old Dark House, and psycho-killer genres, Blood of Dracula’s Castle spends a chunk of its climax emulating the occult films that were popular at the time, as the Count’s clan whip out their hoods and torches as they sacrifice a hapless maiden to the Great god Luna. The scene is executed without the conscious camp that characterises the film as a whole, but still ends up completely lacking in any sort of atmosphere. Finally, the villains are routed, and even here the film screws up: Johnny becomes surely the first werewolf in cinematic history to be killed in his human form, while the vampires die offscreen—the two protagonists describe to us the sight of them ageing and crumbling to dust. Incredibly, the crew behind the film decided that the mute caretaker Mango was interesting enough to become the last villain standing. And so, we are treated to a painfully protected sequence of Glen and Liz being chased across the countryside by the lolloping brute, before the movie finally--finally! —reaches its end. Watching Blood of Dracula’s Castle is not only tedious, but also sad: there are glimmers of humour and inspiration on show, and it is easy to imagine the entertaining Addams Family-esque romp that it might have been had the execution been halfway competent. Instead, all we get is a film that was always destined for oblivion, to be revisited only by monster movie completists. By Doris V. Sutherland

1 Comment

or sharing the article, and more importantly, your personal experience mindfully using our emotions as data about our inner state and knowing when it’s better to de-escalate by taking a time out are great tools. Appreciate you reading and sharing your story since I can certainly relate and I think others can to

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed