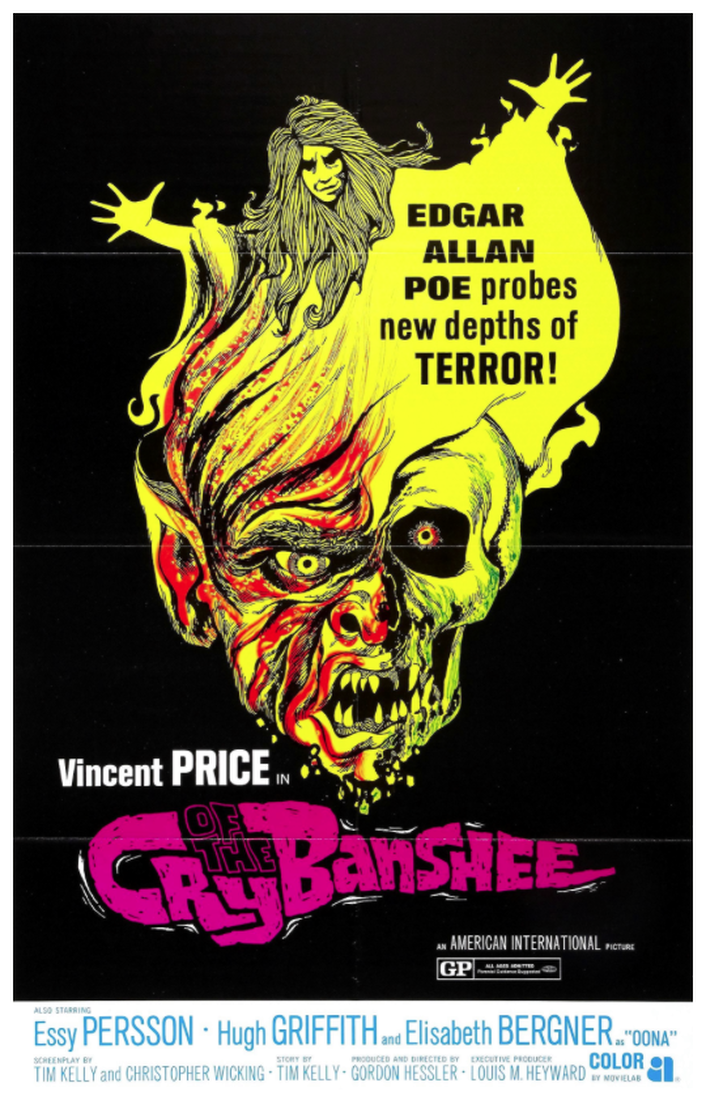

[Tearing Through Werewolf Cinema] 'Cry of the Banshee' Deserves More Recognition as a Werewolf Film1/20/2021  Welcome to a weekly series in which Doris V. Sutherland takes readers on a trip through the history of werewolf cinema... ...Cry of the Banshee (1970) is the story of Lord Edward Whitman (Vincent Price), a sixteenth-century English nobleman who enjoys a life of luxury, debauchery, and the sadistic treatment of women and peasants. But his position of privilege has a drawback: his family is said to be cursed, and all around him are omens. The villagers believe that a cult of witches is active in the area; even though Whitman himself is skeptical, he sees this pervasive fear as a threat to his authority, and so organises witch-hunts. Sure enough, Whitman finds a coven of witches going about their pagan ways and successfully slaughters a number of them. But some survive to set about their revenge. The Whitman household is soon hit by a series of deaths as servant Roderick (Patrick Mower) falls under the power of the witches and becomes a werewolf. The late sixties saw an influx of cinematic werewolves, and, come the seventies, the plague of lycanthropy had not abated. Not all werewolves were able to escape obscurity, however. A Portuguese film called Nympho Werewolf was reportedly released in 1970 but information about it is scanty. Meanwhile, 1971 saw the release of a Brazilian number entitled O Homem Lobo which appears never to have been released in English. And then we have Cry of the Banshee, directed by Gordon Hessler and written by Tim Kelly and Christopher Wicking: a curious example of a werewolf film that seems to have evaded recognition within the subgenre simply because it wasn’t marketed as a werewolf film. Let’s get this out of the way: Cry of the Banshee has little to do with banshees. One scene has a member of Whitman’s retinue blame some (clearly canine) howls on a banshee; the head witch later describes the werewolf (or the spirit inhabiting the werewolf) as a sidhe, the class of Irish fairy that includes banshees; and the general theme of family death-curses is at least adjacent to the banshee motif; but all of this seems thin justification for the name. In any case, it’s unclear as to how a creature of Irish folklore ended up in this rural English village. Cry of the Banshee is a werewolf film, and even though the lycanthrope takes a fair while to appear, the symbols of wolves and rabid dogs permeate the screen. But then, the misleading title is entirely appropriate for a film that seems determined to throw the audience off its trail. The opening titles, which use a quotation from Edgar Allan Poe, announce it as an American International Pictures production starring Vincent Price; so a viewer will likely expect something along the lines of the Price-Poe-Roger Corman cycle. But then comes a credit sequence which, astonishingly, is animated by Terry Gilliam and depicts a Monty Python-style cutout of Vincent Price’s head cracking open while comically eye-rolling demons pour out. Every indication is that Cry of the Banshee will be one of Price’s self-parodies, like The Raven. But anyone expecting light-hearted camp will be instead confronted with a procession of abuse and degradation. In the early portion of the film, we see one woman being branded with a hot iron and clapped in a stock, a second girl getting forced to perform an undignified dance on Whitman’s tale before getting shot dead, and then Whitman’s wife being raped by her own stepson—all when the story has barely started. Far from Gothic theatricality, Cry of the Banshee fits into a cycle of brutal British historical—the Price-starring Witchfinder General is the most obvious comparison point, but the German co-production Mark of the Witch and Ken Russell’s The Devils (released the following year) might also spring to mind. Of course, the likes of Witchfinder General deal with supernatural phenomena as belief, rather than a literal occurrence. Cry of the Banshee eventually heads in a quite different direction by establishing that witches do indeed exist and are in league with Satanic forces. A side-effect of this is that the film gives the audience nobody to sympathise with: the conflict is between the brutal Whitman and the minions of Satan, with the few remotely likeable characters being quickly picked off by the werewolf. Cry of the Banshee is a film that demands patience from its audience. A viewer hoping for the colourful fare of Hammer or Corman might be put off by the grubby squalor, while anyone expecting an indictment of historical atrocities will instead find a fantasy film. Parts of it are easy to scoff at: the first time we see the witches they are frolicking about with skimpy white garments and flowers in their hair, like space hippies in an episode of Star Trek (later scenes do much to improve their presentation, but really, Blood on Satan’s Claw did the same thing better one year down the line). Then we have Whitman’s sidekick, who bears the unfortunate moniker of Bully Boy; this seems like a minor detail until we reach the film’s finale, where an otherwise tense scene is undercut by Vincent Price’s frantic wails of “Bully Boy! Bully Boy! Bully Boy! Bully Boy!” But anyone generous enough to look past these shortcomings may well find Cry of the Banshee a rewarding piece of work. While it invokes a number of better-known films (some of which, in fairness, it predates) it nonetheless builds a coherent and atmospheric world of its own. Its lapses are more than compensated by its frequent moments of surrealism: witness the bizarre scene in which Whitman’s loyalists, having slain a rabid dog, throw a party around the creature’s impaled head—the sight of which causes a female character to suddenly break into insane laughter. Like Hammer’s Curse of the Werewolf the film takes lycanthropy away from Universal-codified clichés and into the twilight of folk belief. The witchcraft connection makes perfect sense, as a large amount of werewolf lore does indeed come from the records of the witch-trials. It is fitting that the lycanthrope is never shown clearly on-screen: while doubtless a budget-saving measure, it also succeeds in making the werewolf an intangible, ethereal presence. Cry of the Banshee deserves consideration as part of the cinematic werewolf canon—and it may well have received that consideration already had the studio entitled it Cry of the Werewolf. By Doris V. Sutherland

1 Comment

zmbdog

7/31/2021 10:18:43 pm

Have you seen an ad or anything for Nympho Werewolf? I'm trying to find at least one thing to prove its existence but I've turned up nothing.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed