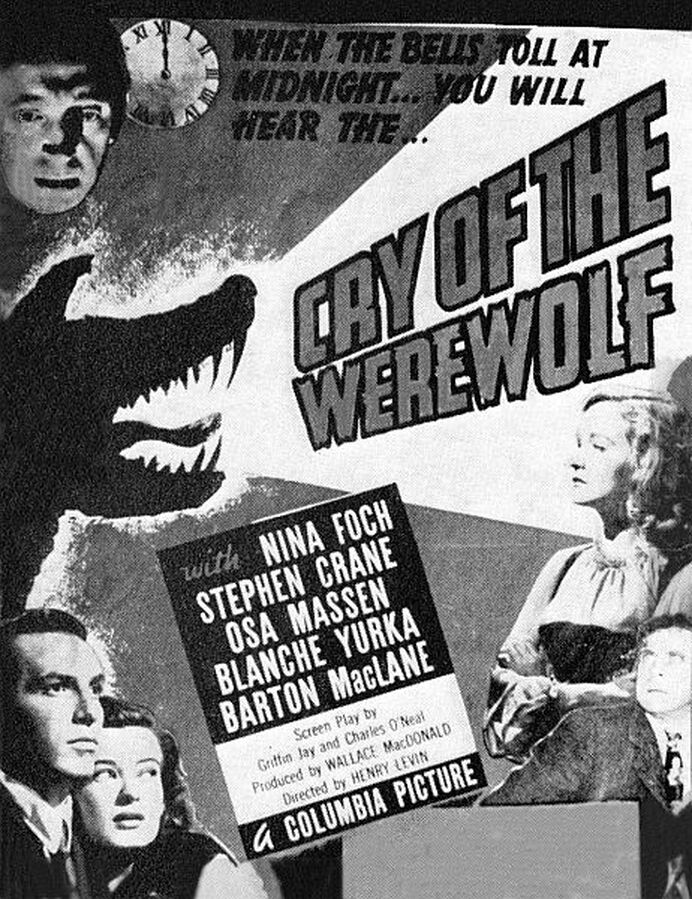

Welcome to a weekly series in which Doris V. Sutherland takes readers on a trip through the history of werewolf cinema... ...In Cry of the Werewolf (1944), Dr. Morris (Fritz Leiber Sr.) of the New Orleans Society of Psychic Research has been found dead inside a hidden passage at his home; the only witness to the murder was his assistant Peter (John Abbott), who lost his mind at what he saw. At the time, Dr. Morris had been studying the history of his house’s previous owner, the alleged werewolf Marie LaTour, so his son Bob (Stephen Crane) sifts through the researcher’s notes in the hopes of finding clues. Meanwhile, police investigating the case suspect Bob’s Transylvanian assistant Elsa (Osa Massen) – but Dr. Morris was actually killed by Princess Celeste (Nina Foch), a member of a local Romani community who turns out to have connections to the legendary werewolf. Shortly after pairing Bela Lugosi with a lycanthrope in The Return of the Vampire, Columbia took another bite of the werewolf genre with Cry of the Werewolf. According to Jonathan Rigby’s book American Gothic, this project started out as a sequel to the earlier film entitled Bride of the Vampire but mutated into something rather different in development. Griffin Jay returns as scriptwriter, this time partnered with Charles O’Neal, while first-timer Henry Levin takes over as director. Sadly, Cry of the Werewolf marks a considerable step back from its atmospheric predecessor: like The Undying Monster, it tries to meld the werewolf genre with the whodunit, with messy results. Much of the first act is spent on dullard hero Bob and some comic relief detectives as they try to find a rational solution to the murder, with Elsa serving as red herring. But the trouble is, the film has already shown us Princess Celeste brooding in her caravan with her adoptive mother, making it perfectly clear who the real culprit is. There are a few questions at this point – the exact nature of Celeste’s relationship to Marie LaTour, for one – but nothing with sufficient intrigue to sustain a mystery story. Once the detective business is dropped and Celeste is allowed to take centre stage, things get a little more energetic. Celeste uses her dark magic to win over Bob’s heart and turn Elsa into her slave, creating a diabolical love triangle. Nina Foch’s portrayal of Celeste is reasonably engaging – sometimes an eyelash-fluttering ingénue, other times a femme fatale – but any credibility the film tires to build is ruined by Stephen Crane, whose hilariously awful performance as Bob really has to be seen to be believed. He doesn’t appear to have taken the part at all seriously. Despite all of its shortcomings, Cry of the Werewolf has a degree of curiosity value. Aside from being the earliest surviving film to feature a female werewolf, it’s notable for depicting a distinctly pre-Universal lycanthropy, drawing inspiration not from Lon Chaney Jr. but from the werewolves of folklore and literature. The film’s werewolves turn into actual wolves, not people with fur and fangs; they transform at will through black magic, not during a full moon. Their condition is hereditary, rather than an infection passed through bites, recalling vintage Gothic fiction and its love of family curses. Meanwhile, the prologue sequence of Marie LaTour’s husband following a trail of wolf prints only to find his wife at the end feels like something out of a witch-hunt trial. Cry of the Werewolf could have been a worthy addition to the genre had it shown more faith in its supernatural subject matter. Instead, it falls back on murder mystery melodrama that prompts yawns rather than chills. By Doris V. Sutherland

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed