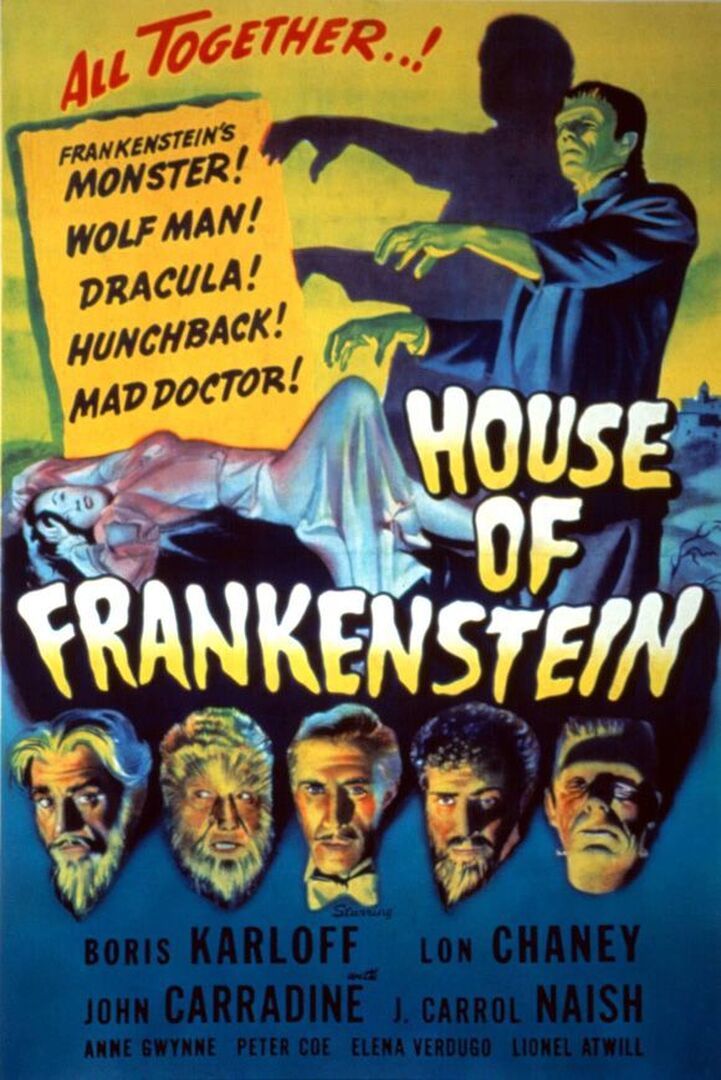

Welcome to a weekly series in which Doris V. Sutherland takes readers on a trip through the history of werewolf cinema... ...House of Frankenstein (1944) opens with mad scientist Dr. Gustav Niemann (Boris Karloff) and his hunchbacked assistant Daniel (J. Carroll Naish) escaping from their prison cell, after which they commandeer a travelling carnival and journey across the countryside. Along the way, they pick up a number of misfits: Count Dracula (John Carradine), Romani runaway Ilonka (Elena Verdugo) and werewolf Larry Talbot (Lon Chaney Jr.). Each of these travellers has something that they hope to gain from Niemann, but the scientist turns out to be more interested in punishing the men who sentenced him to prison. When he eventually finds Frankenstein’s Monster (Glenn Strange) he begins to put his plan into action. “All Together! Frankenstein’s Monster! Wolf Man! Dracula! Hunchback! Mad Doctor!” proclaimed the posters advertising House of Frankenstein upon its release. And really, this sums up the film’s main purpose: to outdo its predecessor Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man by pulling together a still larger selection of recurring characters and archetypes. Storyman Curt Siodmak, screenwriter Edward T. Lowe and director Erle C. Kenton were faced with the unenviable job of getting a workable story out of this monstrous ensemble – so just how well did they succeed? Well, there are inevitable points at which the film is straining at its seams. The biggest casualty is Dracula, who gets written out only a short distance into the narrative: his entire story arc is dropped, the young couple he menaces never seen again, and he doesn’t even appear onscreen with the Wolf Man or Frankenstein’s Monster. When House of Frankenstein finally pulls itself together, it does so by borrowing. Niemann shares his M.O. – picking off the men who sentenced him – with Ygor from Son of Frankenstein. Larry Talbot’s yearning for death is re-used from Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man. Daniel’s tragic infatuation with the Romani girl owes something to The Hunchback of Notre Dame – although admittedly the film one-ups its source here by putting the two characters in a love triangle with a werewolf, a plot twist probably never contemplated by Victor Hugo. These weaknesses are extremely easy to point out – and, if you watch the film in the right spirit, extremely easy to ignore. House of Frankenstein succeeds in its modest ambition of being just all-round good fun. The cast does much to elevate the script. Boris Karloff plays Niemann less as a stereotype, more a platonic ideal: the b-movie mad scientist in his purest expression, putting genuine glee into the most risible lines of dialogue (“I’m going to give that brain of yours a new home in the skull of the Frankenstein Monster! As for you, Strauss, I’m going to give you the brain of the Wolf Man!”). Lon Chaney Jr, although tasked merely with repeating material from the previous Wolf Man films, puts in a watchable performance. J. Carroll Naish also deserves a word of praise as the hunchback Daniel, who ends up bearing a surprising amount of the film’s emotional weight come the final act, when he is spurned by both Niemann and Ilonka. And while John Carradine is no Lugosi, his staring-eyed pantomime Dracula has some charms and clearly left a mark on audiences: Carradine was hired to reprise the role in multiple films both in and out of Universal. House of Frankenstein is also something of a last hurrah for Universal horror. Granted, it wasn’t the last of the studio’s Dracula-Frankenstein-Wolf Man cycle, but it was the last to fully embrace the Gothic: its follow-ups would make a stab at scientific rationalisation (House of Dracula) before ending up as outright comedy (Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein). Even at its most derivative, the film has the excuse of being an opportunity to give the old favourites one last run. By Doris V. Sutherland

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed