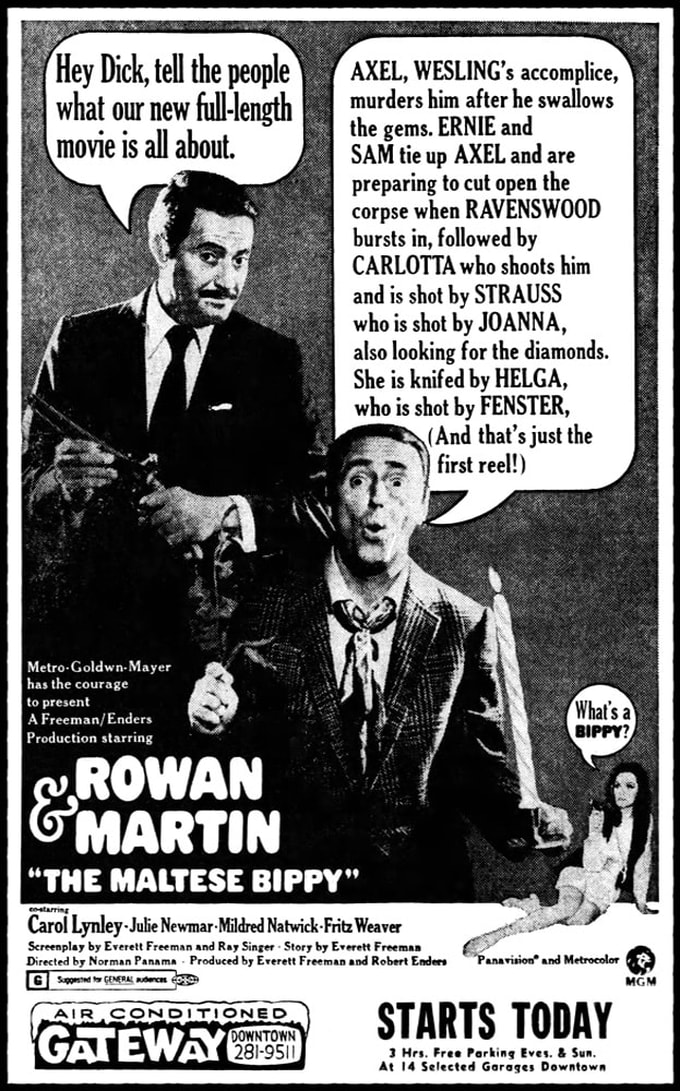

Welcome to a weekly series in which Doris V. Sutherland takes readers on a trip through the history of werewolf cinema... ...The Maltese Bippy (1969) opens with a scene set in twelfth-century Mongolia, where the warlord Irving the Horrible reigns as tyrant over his oppressed subjects. An onscreen caption informs us that this has absolutely nothing to do with the rest of the film, and we cut to the real prologue: a woman being attacked in a graveyard by a mysterious killer. Next comes a sequence of the two stars Dan Rowan and Dick Martin trading banter over the opening credits—all of which should make it clear to us that, as far as werewolf films go, The Maltese Bippy isn’t the straightest-faced specimen. The film casts Martin as an actor reduced to appearing in shoestring-budget porn films for sleazy producer Rowan. While shooting an erotic sci-fi adventure, which involves wooing an alien princess before the painted backdrop of the moon, Martin suddenly finds himself howling. It later turns out that bodies being found in the area are mauled and partly eaten, leading to speculation that a werewolf is abroad. Martin is terrified at the prospect that he has become a man-eater, but Rowan is captivated by the showbiz potential of a star who can turn into a wolf before the audience’s very eyes. Meanwhile, the two share their tenement housing with various eccentric and sinister individuals, any one of whom could be the lycanthrope—so if Martin isn’t a werewolf, he may well end up on the menu himself. The Maltese Bippy is a vehicle for the two stars of the television sketch comedy Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In, the debut season of which had aired the previous year and was a runaway success. Director Norman Panama (an established comedy talent best known for his collaborations with Melvin Frank, including The Court Jester) teamed with writers Everett Freeman and Ray Singer to adapt the double act for the big screen, and in doing so, was faced with the obvious hurdles that come from turning a sketch comedy into a feature film. Starting out with a palpably Pythonesque “and now for something completely different” moment and ending with a five-minute assault on the fourth wall, The Maltese Bippy inherits something of the fragmented nature of its source material. Martin’s character arc riffs on stock plot situations from Universal’s werewolf films, while his only onscreen transformation, occurring in a dream sequence, turns him into a cartoonish, low-budget version of the Werewolf of London. But when sibling lycanthropes Fritz Weaver and Julie “Catwoman” Newmar turn up, their portrayal owes more to vampire films: Weaver performs his character as a Lugosian figure who boasts of being centuries old, while Newmar looks as though she’s crawled out of a coffin in a Hammer studio. The film actually turns its conflation of vampires and werewolves into a running gag, the dream sequence ending with a cloaked Rowan hammering a stake into Martin’s heart (“That’s for vampires!” pleads the latter shortly beforehand). So, while the werewolf spoof element is the closest thing to a central concept in the film, The Maltese Bippy is never really as dedicated to lampooning horror conventions as was Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein from two decades beforehand. Abbott and Costello treated their monsters with a certain respect; but to Rowan and Martin a werewolf is just one more wacky outfit in the studio wardrobe. That said, the film manages to get some novel gags out of the lycanthropy through Rowan’s character, the hard-up film producer who hopes to make it big exploiting werewolves. The creators clearly poured their first-hand familiarity with the less glamorous aspects of showbiz into Rowan’s material: some of the jokes have aged badly (a film producer tempting nubile young women with job offers seems rather less amusing in the post-Weinstein era) but the fast-paced, generally good-natured humour mostly stands up. One memorable exchange has a financial backer turning down Rowan’s proposal on the grounds that a werewolf can only perform at night—and what good’s an animal act that the kiddies can’t watch? In another sequence Rowan meets up with Julie Newmar’s character, eager to see her transformation into a wolf (even though, by that point, the audience knows she’s not a real werewolf after all). When his back is turned, Newmar walks out of the room, and a large, extremely well-groomed dog walks in. Predictable? Sure. But it’s executed so smoothly that you’d have to be a bit of a curmudgeon not to at least crack a smirk. As the werewolf jokes start to grow stale, the film begins foraging for fresher material with mixed results. One misjudged sequence has Martin (hypnotised by David Hurst’s Van Helsing-like character) try to throttle Carol Lynley’s heroine before giving chase as she tries to escape; until Martin bonks his head and regains his memory, this is played completely straight and strikes a discordant note in a film where even the death scenes are silly. Eventually, The Maltese Bippy becomes the story of skullduggery surrounding a hidden treasure, as implied by its title, and finds an amusing premise: a whodunit where just about everyone is guilty of something. Although Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In continued until 1973, the double act never again made a film together. Watching The Maltese Bippy, even the most indulgent viewer is unlikely to find this surprising: the duo’s natural home was on the small screen, in small chunks. But while not exactly a timeless classic of comedy, the film remains an amusing romp; and in relation to the horror genre, it is a notable artefact from a period in which werewolf comedy was finding a home outside of Universal’s self-parodies. By Doris V. Sutherland

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed