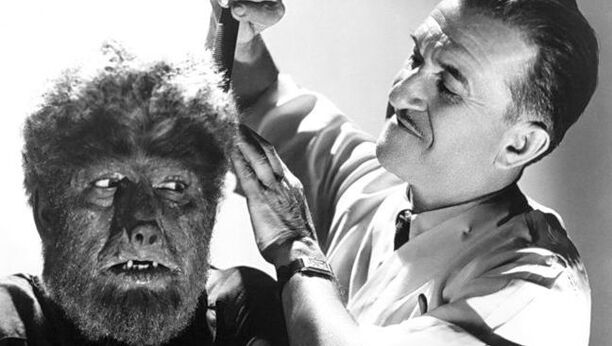

[Tearing through Werewolf Cinema] Universal Created the Definitive Werewolf Film with 'The Wolf Man'6/24/2020  Welcome to a weekly series in which Doris V. Sutherland takes readers on a trip through the history of werewolf cinema... ...Following the death of his brother, estranged aristocrat Larry Talbot (Lon Chaney) returns to his family estate in rural Wales. During a trip to the nearby forest, he is bitten by a wolf which he kills using a silver-headed cane. When he recovers, he learns from the police that there is no dead wolf at the site of the incident – only the body of a man named Bela (Bela Lugosi). It turns out the creature killed by Larry was both man and wolf – a werewolf. Through its bite, it had passed its curse onto him. The Wolf Man (1941) came at a time after Universal horror had begun to rely on sequels. Bride of Frankenstein and Dracula’s Daughter had each been worthy follow-ups, but Son of Frankenstein and The Mummy’s Hand had been less inspired. Considering that Werewolf of London was itself a flawed piece of work, any viewers at the time who had low expectations for this spiritual successor could be forgiven. But as it turns out, The Wolf Man improves on its predecessor in almost every way. The film has the same general narrative shape as Werewolf of London – the curse spreading rabies-like through a bite, the transformation at full moon, the protagonist’s path to inevitable destruction –but it trims the fat. Gone is the business of the werewolf messing about growing plants in a laboratory in hopes of finding a cure. The elder lycanthrope is swiftly killed after passing on his curse, preventing the film from being bogged down with two werewolves as its predecessor was. The film also makes some new additions to the lore of werewolf cinema: although the association between lycanthropes and pentagrams (serving as a protective charm and as a marker for the next victim) never really caught on, the notion that werewolves can be killed by silver bullets most definitely did, transformed from a fairly obscure piece of folklore to a genre convention. Lon Chaney Jr. was pigeon-holed as a horror star on the basis of his family name, but it’s hard to argue that monstrous roles came naturally to him: without the aid of slathered-on makeup, he was only truly convincing as an Igor-like henchman (as in Black Castle) when he could channel his earlier performance as Lennie in Of Mice and Men. But his turn as Larry Talbot works precisely because the character isn’t monstrous. He is a typically laid-back, somewhat gormless everyman, making a strong contrast with his lupine alter ego. Admittedly, it’s a little hard to swallow the all-American Chaney as the son of a British lord, but the film at least tries to address this by establishing him as a prodigal son – the fruit having fallen very far from the Talbot tree, apparently ending up across the Atlantic. (Meanwhile, the reason for the Welsh townspeople having English accents is left undivulged.) Jack Pierce’s makeup job on the werewolf is again a standout. Other than an unfortunately weak transformation scene (achieved through, of all things, a close-up of Chaney’s feet) this Wolfman is more impressive-looking than his 1935 counterpart. Meanwhile, his surroundings are the usual mist-clad Gothic milieu that horror fans had come to expect from Universal. From the film’s visuals to the script’s refinements of werewolf lore, everything in The Wolf Man comes together: It’s no exaggeration to say that screenwriter Curt Siodmak and director George Waggner, along with Chaney and Pierce, did for werewolves what Bram Stoker did for vampires. The Wolf Man is also perhaps the bleakest entry in the Universal horror canon, with its grim narrative of one man’s journey towards destruction. While many earlier horror films had dealt with people becoming monsters, most of them were guilty of some transgression (as in the various mad scientist films) or, if innocent, they were ultimately cured or at least avenged (as with Dracula’s victims). In The Wolf Man, however, the transformation is brought about through sheer bad luck, rather than a personal failing on Talbot’s part. Werewolf of London had the same narrative arc, of course, but the effect was dampened by Henry Hull’s rather stiff performance. Chaney’s likeable turn as the everyman werewolf makes his plight all the more pitiable. With The Wolf Man, Universal created the first truly iconic addition to its monster pantheon since the Bride of Frankenstein in 1935, and the last until the Creature from the Black Lagoon in 1954. But more than that, the studio created the definitive werewolf film. By Doris V. Sutherland

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed