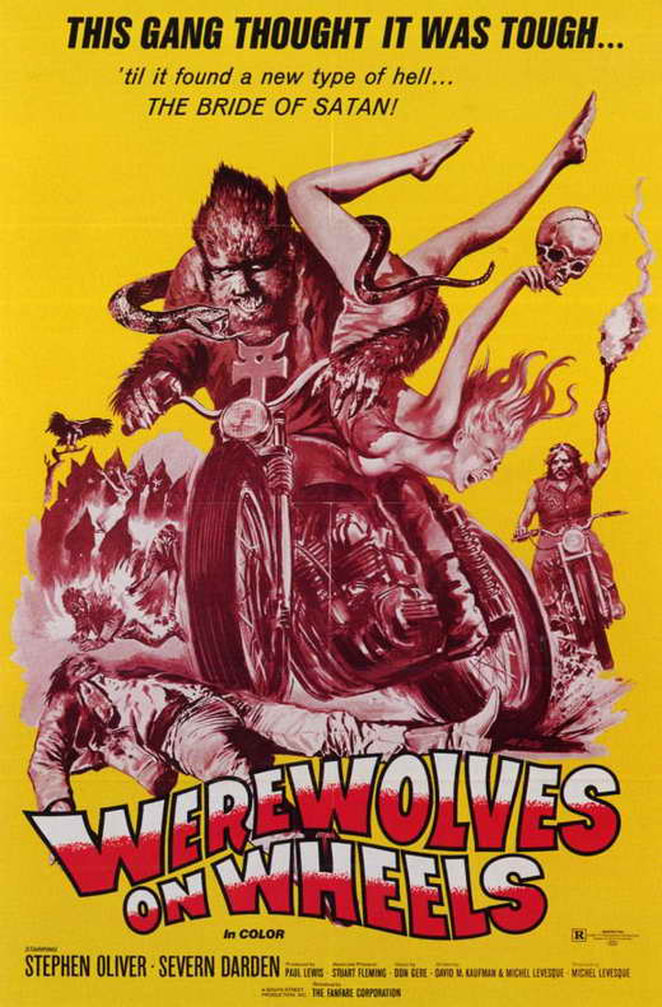

Welcome to a weekly series in which Doris V. Sutherland takes readers on a trip through the history of werewolf cinema... ...Werewolves on Wheels (1971) is the story of a biker gang that rides through the wilderness looking for kicks. Along the way, the motorcyclists stumble upon a fellow band of rebels, albeit ones of a very different stripe: a cult of devil-worshippers led by the high priest One (Severn Darden). The bikers disrupt the Satanists’ ritual and head on their way, only to find that they’ve taken a bit of black magic with them. Once they start falling victim to gruesome murders, the gang has to face up to the fact that one of their number has become a werewolf. Created by writer-director Michael Levesque and co-writer David M. Kaufman, Werewolves on Wheels starts out looking like one of those films where you know exactly what to expect. We have that perfect trash-epic title, while the first shot is of a desert highway with a blurry biker gang in the background and moody guitar-strumming on the soundtrack. It looks like we’re all set for that specific flavour of punkish seventies horror explored by the early works of Tobe Hooper and Wes Craven, and later homaged by the likes of From Dusk till Dawn. But what we get turns out to be a different beast altogether. To start with, the film makes the surprising move of almost completely foregoing the stereotype of biker gangs as violent. The characters are hedonistic and self-centred (witness the scene in which it doesn’t occur to them to pay the owner of the petrol station they fill up at) but not particularly aggressive. Instead of picking fights, they largely ignore the wider world as they drive aimlessly through the desert, their minds on little more than the next beer, the next spliff, and the next lay (a sexually liberated gang, the bikers even have a gay couple in their number). This saga is shot partly in a post-psychedelic haze, but also partly in a naturalistic, even pseudo-documentary style to give the impression that we’re seeing an unfiltered vision of a typical biker gang’s existence. The film often resembles Easy Rider more than any of its more obvious exploitation brethren. Adding a subplot about a cult of devil-worshippers to Easy Rider is not quite as outlandish as it might seem. When Werewolves on Wheels came out in 1971, Anton LaVey’s Church of Satan had been active for only five years, while the Manson Family murders (widely if misleadingly reported as the work of Satanists) occurred just three years beforehand. To the mainstream public, sects of homicidal diabolists were just as much a part of the countercultural landscape as stoned motorcyclists. Indeed, the Satanic ritual sequence is shot with a similar quasi-documentary aesthetic to many of the scenes involving the bikers. The infernal priest pointedly spells out exactly which chants to use, which sigil to draw on the floor in blood, and even the correct type of wood to make a ritual chalice. It’s almost as though we’re watching a Do-It-Yourself Demon-Summoning VHS. And dropped right into this pseudo-realistic examination of post-summer of love West Coast subculture is a werewolf. Granted, there isn’t a great deal of lycanthropy in the film. The werewolf doesn’t appear until about forty minutes in, with his second appearance coming a full hour of the way through; we don’t even get a clear look at him until the final minutes. But still, he’s present and correct in what is, on the whole, the last film you’d expect an old-school Chaney-Pierce wolfman to pop up in. We can only imagine the behind-the-scenes decisions that led to Werewolves on Wheels: did the creators start work on an unsensationalised, naturalistic examination of the contemporary biker scene, and then reasoned that the crucial ingredient it needed was a Universal monster? Or did they set out to make a b-movie about lycanthrope bikers, and then get so distracted by the romantic rebellion of these petrolheaded outlaws that they nearly forgot the werewolf? With a little effort it’s possible to tease some sort of thematic logic out of Werewolves on Wheels. The biker played by Deuce Berry is an avid tarot-reader, so much so that his character is nicknamed Tarot, and the film’s first scene of substantial dialogue involves him delivering a card-reading. The gang later begins fracturing along ideological lines, with Tarot’s free-form spiritualism on the one side and a macho materialism on the other. When the bikers start falling victim to the werewolf, this can be seen as punishment for rejecting belief in the supernatural. A particularly generous viewer might even read Werewolves on Wheels as a parable about the sidelining of subcultural spirituality as the sixties segued into the seventies. A less generous viewer, on the other hand, may well see the film as a meandering and aimless piece of work that sometimes stumbles into the occasionally effective scene. Whatever its shortcomings, anybody who appreciates a truly offbeat monster movie will get a kick out of Werewolves on Wheels. By Doris V. Sutherland Please consider joining us in celebrating Black History Month by donating to BlackLivesMatter.com

1 Comment

|

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed