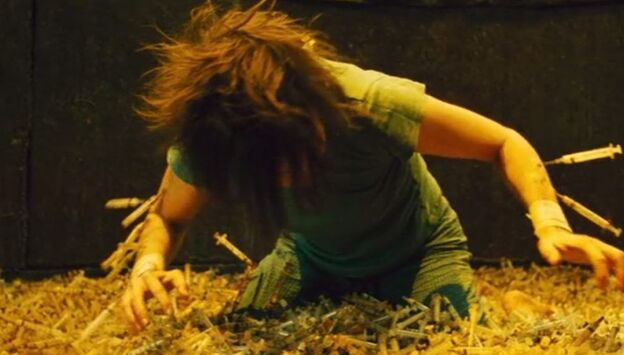

“Don’t forget the rules…” intones grim mastermind of ironic torture John Kramer (Tobin Bell), aka the Jigsaw Killer, at a crucial moment in Saw II (2005)... ...During the scene in question, John is reminding belabored detective Eric Matthews (Donnie Wahlberg) that if he wants to see his son Daniel (Erik Knudsen) alive again, he must play what is perhaps Jigsaw’s simplest game in the entire franchise: “just sit here and talk to me.” As anyone who has seen the film knows, Eric is unable to obey this one crucial rule, and the consequences are dire for everyone involved. Happily, the film plays by its own rules, the rules of what would become an eight-film franchise with a ninth on the way, and not only succeeds as a result but cements its place as the best of all the Saw films, original included. When people packed into theaters to see Saw II during that late October opening weekend fifteen years ago (and believe me, I was there—every screening was JAMMED), no one could have predicted the movie would make almost $150 million worldwide, or what the franchise would become, but the signs were certainly there. The premiere of each new Saw was an absolute event, and that level of hype began with Saw II. Nowadays, that sort of high-key excitement, the self-aware cultural moment as it were, is reserved almost exclusively for Marvel movies and Chris Pratt playing Turner-and-Hooch with extinct apex predators. But audiences absolutely had to know, after that now-classic, jaw-dropping twist from the end of Saw, where did the story from James Wan and Leigh Whannell’s little-horror-film-that-could go next? As it turns out, it went grungier, gorier, and grander; but not so grand that it lost focus and slipped into showcase of spectacular set pieces like every installment from Saw III (2006) onward. The traps in Saw II serve the story, acting as touch points for the narrative of the film but never detracting from either character or story. This would become the inverse as the franchise progressed, with plot and performance built around increasingly elaborate and showy death games that come off as silly and cartoonish. In this film, the traps are accessories—diabolically interesting accessories, to be certain—but the pull is the setup and watching characters attempt to navigate a nightmare. The nerve gas house serves up just enough carnage and shock to earn that specific brand of Saw sadism without dipping into violence for the sake of violence. The most anxiety-inducing moment in the film doesn’t even involve gore or blood but a hidden pit full of used needles, and the added nausea in seeing the brutish Xavier (Franky G) fling the earnest and doubly victimized Amanda (Shawnee Smith) into said needles when the trap was designated for him. It’s a fast, visceral, and dark moment and perfectly emblematic of the film as a whole. There’s a gut-punch physicality to Saw II that didn’t quite exist in the more cerebral original, where the games are more ritualistic. It’s a bold stance that the film takes in the bone-chilling opening sequence featuring the Venus flytrap device, and doesn’t let up from there. Within ten minutes, the film is successfully subverting expectations once again with the capture of Jigsaw. Giving Bell more to do than just be a creepy voice on some tapes was a great move on the filmmakers’ part, and not one many people expected at the time. It’s his performance in the tete-a-tete with Eric that gives the film its police procedural/psychological thriller/morality play angle that sits in harmonic contrast to the garish goings-on inside the nerve gas house. Whereas the first film played as a mystery concerning Jigsaw’s identity, Saw II boldly provides us the answer, once more twisting expectations in revealing John’s backstory and the circumstances that led him to adopt this heinous form of rehabilitation. It’s life coaching gone gruesomely wrong, but we can’t deny the color it adds to John’s character and to the mythos of the franchise as a whole. John is a horrifying villain, yes, but he’s also strangely compelling. Pulling the veil back on Jigsaw also lulls the audience into a false sense of security. This central question is being answered, and though we’re primed to expect a twist, we have no idea what form that twist will take. This results in Saw II being the most puzzle-like of any of the films in the franchise. Whereas in so many of the sequels we’re merely watching the game, cringing at the deaths, and waiting to have the rug pulled from under us, in Saw II we’re playing along with the characters, and we’re not attuned enough to the beats of the series yet to know what we should be looking for in regards to the ending. It’s another example of solid narrative inversion executed expertly. This is not to say that the film isn’t without its plot inconsistencies, but they’re minor and don’t break the world in the way that some of the forced twists in future films would stretch credulity, though I’ve always been inclined to forgive small narrative flaws when presented with great visuals, and Saw II boasts an excellent production value. Director Darren Lynn Bousman goes bold and brave, utilizing lots of corners and shadow play to make the dingy, rusty sets look even more dangerous. The notable sickly color scheme is also back in this film, which elevates that palpable sense of claustrophobia and dread both in the house and in Jigsaw’s lair, especially as the SWAT team realizes they’ve lost complete control of the situation, if they ever really had any to begin with. Which brings us to the twists, of which Saw II has so many that the iconic “Hello, Zepp” theme is played twice. I’d argue that all of the twists here go off without a hitch, and pack harder punches than the ending of the first film, but there’s one in particular that cements Saw II’s legendary legacy. SPOILERS BELOW FOR THE ENDING OF SAW II And I’m referring, of course, to Amanda. I mean, did anyone expect her to be in on the game? And not just that, but to be Jigsaw’s apprentice, the person chosen to carry on his work after his approaching death. To this day I can recall the collective gasp in the theater when it was her voice, not Jigsaw’s, which came on the tape in the bathroom. It was the hiding-in-plain-sight/The Usual Suspects twist taken to the next level, and while seasoned moviegoers these days might be apt to scoff at such a revelation, or be too savvy to get taken in by the ruse, Amanda’s involvement came as a major blindside back in 2005. Perhaps it’s because audiences at the time—and even today, arguably, though probably less so—were less likely to expect a female villain. That John designates Amanda as heir to his legacy is certainly significant, especially as the mythology of the series expands and we discover that John trained multiple apprentices, all of them male, none of them given Amanda’s place of honor, but aside from the feminist angle, the twist works so well because it’s so masterfully well hidden. The character of Amanda is a convincing actress. After her initial questioning when it becomes apparent she has knowledge about their situation, no one in the nerve gas house suspects Amanda of being their captor. She appears just as distraught and devastated as the rest of them to have found herself in this predicament (and in many ways, she is, but we’ll get to that momentarily). Meanwhile the audience, much like the characters, is awash in a mix of pity and sympathy for seeing this character have to endure Jigsaw’s cruelty once again. In rooting for her to survive, we don’t give as much credence to the film’s clues as we should. Amanda’s manipulations of the others disguised as advice. Her lack of side effects to the nerve gas poisoning. Shielding Daniel from a deranged Xavier. There’s one moment, though, that shows us how much deeper things go with Amanda, and with the philosophical underpinnings of the Saw mythology. It’s when Amanda first wakes and her hands fly to her head in a panic, checking to make sure she is not once again trapped in that dismal dungeon wearing the reverse bear trap. This gesture is so telling of Amanda’s character because in this moment, she is her real self. Her raw, emotionally scarred self. As we know, the others didn’t know of her or her previous experience with Jigsaw. Some of them didn’t even know who Jigsaw was, so performing a callback gesture for the others’ benefit would be unnecessary. This is how we know the moment is genuine. Amanda is deeply psychologically affected by her first encounter with Jigsaw, as we would expect anyone to be. She was kidnapped, drugged, strapped into a device that could have torn her skull to pulp, and forced to cut open an innocent man in order to survive. As we see in flashback during the events of Saw II, this left Amanda not with a revelatory appreciation for her life, but a trauma so deep and so painful, she relapses into self-harm and attempts to take her own life. This is a not uncommon response for real-life victims of trauma that are unable to access helpful, positive resources to cope with their experiences. It’s also perhaps one of the most essential story points in the Saw franchise because it shows us firsthand that Jigsaw’s process doesn’t work. John selects Amanda as his apprentice and heir because he sees in her proof of his methods and his philosophy. She is the sole survivor of any of his games and so, he reasons, he has changed her so fundamentally that not only has she seen the “error of her ways,” but has seen the method to his madness and will help him “save” others. But John is projecting, seeing what he wants to see. If Amanda had truly “met death and been reborn,” as John believes she has, why then would she try to end the life she had just reclaimed? It’s because trauma of the horrific kind Jigsaw is forcing on those he deems unworthy of their lives, doesn’t work that way. His games don’t give people their lives back, it destroys them so severely they’re left courting death as a means to escape the pain. John considers Amanda his greatest success story, but she’s actually the perfect example of why his methods don’t work. Trauma is the legacy John bestows upon Amanda, not his traps. For how sick and twisted the world of the Saw films is, there is a certain comfort in knowing that hidden away in Saw II is this moment that reads as denial of Jigsaw and his demented philosophy. John may claim moral integrity and hide his psychopathy behind his traps, and behind Amanda, but she is living proof that his work is not just monstrous, it fails. Suffering begets only more suffering. We see this play out quite explicitly in Saw III, but the seed of that fruit is actually planted here in this film. Saw II is the rare horror sequel that matches its predecessor without dishonoring its accomplishments. Remembered for its traps and its twists, it also has the most narratively literate story in the franchise and a subtle yet powerful underling message on the effects of severe emotional suffering. It’s a sharp, effective film that twists elements of psychological horror with grimdark gore to produce a bloody, grisly, and nightmarish entry that stands far and above its sister films. Somehow grimy yet slick, repulsive while still being icy cool. So don’t forget. Saw II rules. By Craig Ranallo

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed