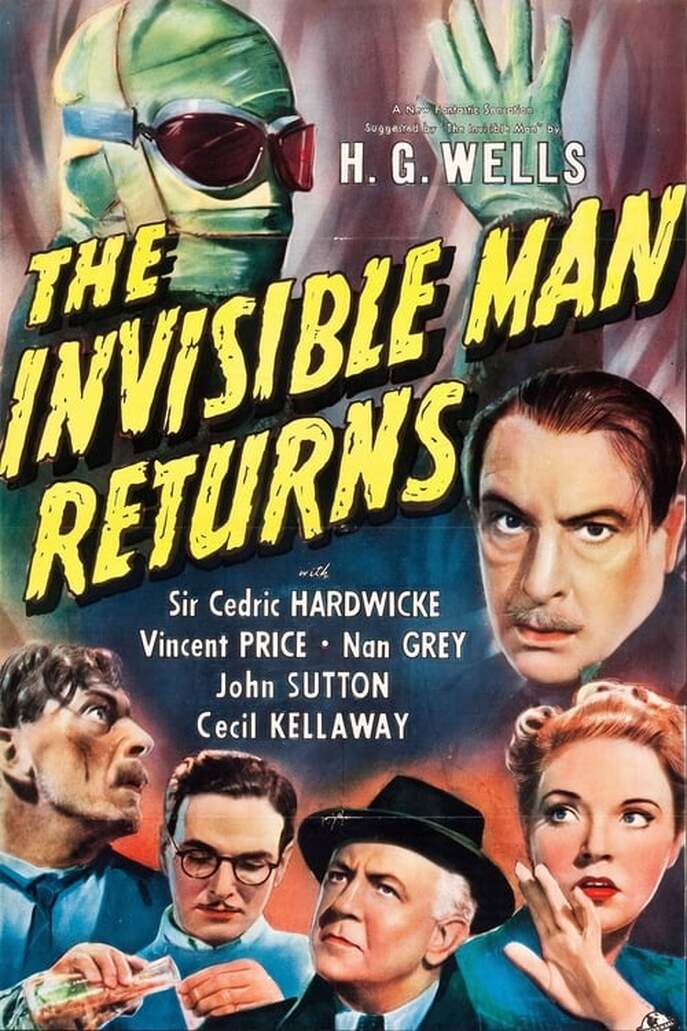

The Invisible Man Returns (1940) is set nine years after the events of the original film... ...The Invisible Man Jack Griffin is long dead, but his brother Frank (John Sutton) still has access to his formula. When Frank’s friend Sir Geoffrey Radcliffe (Vincent Price) is sentenced to death for a murder he didn’t commit, the noble scientist arranges a jailbreak by injecting him with the formula during a visit. The plan has a drawback, however, as the freed Geoffrey has no known means of regaining visibility. Worse than that, the serum is gradually driving him insane, just as it turned Jack Griffin into a homicidal maniac. While Geoffrey fights to clear his name, Frank struggles to develop an antidote before it’s too late… In the latter half of the 1930s, Universal realised the sequel potential in its pantheon of monsters. Bride of Frankenstein came out in 1935, with Dracula’s Daughter following in 1936 and Son of Frankenstein in 1939. Come 1940, the studio dug further into its back-catalogue—resulting in this sequel to The Invisible Man, released seven years after the original. H. G. Wells never wrote a sequel to the novel on which the first film was based, and although there were other stories about invisible men that could have been adapted (including Philip Wylie’s The Murderer Invisible, which Universal had the rights to at one point) the team behind The Invisible Man Returns opted to tell an original story that picks up where Wells left off. Director Joe May (teamed up with screenwriters Curt Siodmak and Lester K. Cole) was given the task of filling the considerable shoes left by James Whale, who directed the original film. Right from the start, it becomes apparent that Whale’s brand of ghoulish camp is absent: instead of the mysterious and sinister Jack Griffin arriving at a rural inn, we get a string of dialogue scenes to establish the sequel’s backstory as clearly as possible. So, The Invisible Man Returns is less of a horror film than its predecessor, and more of an innocent-man-on-the-run crime melodrama that happens to have invisibility as a plot device. As an example of this genre, though, it turns out to be entirely solid. The storyline has enough twists and turns to retain interest, and the film’s usage of invisibility is sufficiently inventive to prevent it from merely re-treading the 1933 outing. One scene that sums up its imaginative approach to the motif involves Frank Griffin testing his cure on an invisible guinea pig—portrayed by an empty harness and some dubbed-on squeaks. One more thing that’s worth pointing out is that the sequel redeems a weakness of the original. In adapting Wells’ novel, Universal introduced the idea that Griffin’s invisibility serum drives the user mad, which merely cheapened the character and has often been criticised (Wells himself certainly wasn’t pleased). This plot point is re-used in The Invisible Man Returns, and to good effect. While it was impossible to see Jack Griffin as having ever been anything other than a megalomaniac, Sir Geoffrey is a tragic figure: a decent man slowly being turned into a murderer by the drug that was his only means of escaping death. The psychological cost of the invisibility serum becomes a metaphor, as it symbolises the way in which Geoffrey is driven to ever-deeper desperation by his existence as a fugitive. The Invisible Man was not an easy act to follow, but The Invisible Man Returns manages to find its own spin on the basic premise. While not quite the enduring classic that the original became, the sequel is at least a worthy footnote. By Doris V. Sutherland Celebrate Women in Horror Month with us by donating to Cinefemme at: Donate (cinefemme.net)

1 Comment

for sharing the article, and more importantly, your personal experqdqwd ience mindfully using our emotions as data about our inner state and knowing when it’s better to de-escalate by taking a time out are great toosdcdavals. Appreciate you reading and sharing your story since I can certainly relate and I think others can to

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed