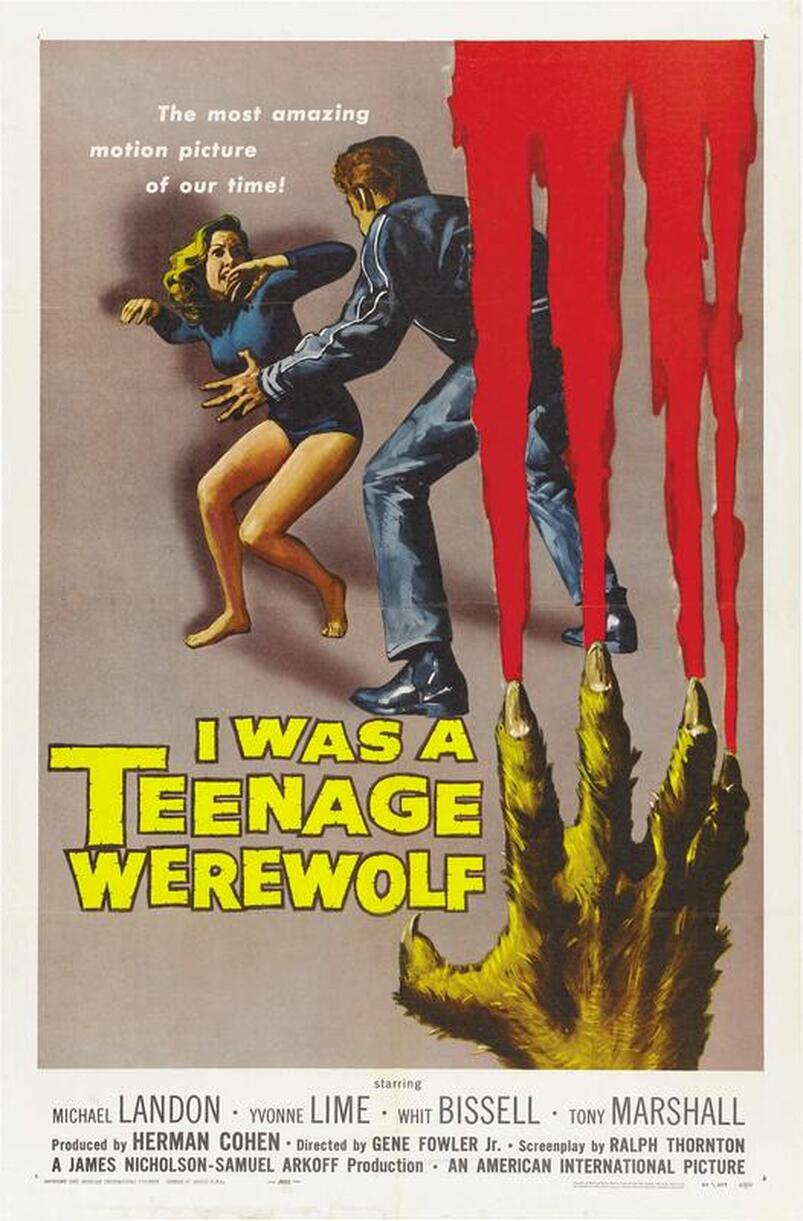

Welcome to a weekly series in which Doris V. Sutherland takes readers on a trip through the history of werewolf cinema... ...In I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957), Tony Rivers (Michael Landon) is a troubled young man prone to getting into fistfights with other students at Rockdale High. At first, he brushes off advice to seek therapy, but after beating up a friend for a harmless Halloween prank, Tony realises he has problems that need seeing to. Unfortunately for him, the local psychologist Dr. Alfred Brandon (Whit Bissell) is not in the business for altruistic reasons. The doctor wants to use Tony as a guinea pig for a bizarre experiment: “Through hypnosis, I’m going to regress this boy back, back into the primitive past that lurks within him. I’m going to transform him and unleash the savage instincts that lie within! Then I’ll be judged a benefactor. Mankind is on the verge of destroying itself. The only hope for the human race is to hurl it back to its primitive dawn, to start all over again.” The procedure is a success from Dr. Brandon’s point of view, but a terrible failure from the perspectives of Tony and his classmates: far from finding his violent urges quashed, he is now prone to turning into a hairy, fanged, and very bloodthirsty werewolf. Directed by Gene Fowler Jr. from a script by Aben Kandel and producer Herman Cohen, I Was a Teenage Werewolf has obvious similarities to the previous year’s The Werewolf, another attempt to revive the long-dormant werewolf subgenre by moving it from Universal-approved Gothic backdrops to modern small-town America. Indeed, the two films’ villains even share a single, very specific motivation: they’re turning people into werewolves as a misguided response to the threat of nuclear annihilation. But I Was a Teenage Werewolf has one thing its predecessor lacked. It’s something that’s right there in the film’s title (which, as an aside, is a brilliant title, one that sits alongside It Came From Outer Space and Attack of the Fifty Foot Woman in the ranks of most frequently parodied B-movie titles). And it’s something that brought werewolf cinema bang up to date. That vital ingredient is teenage angst. The film is hardly subtle about the correlation between Tony’s lycanthropy and his bubbling adolescent hormones. His first onscreen transformation occurs after seeing an attractive young woman in gym gear, like he’s a live-action version of Tex Avery’s horny cartoon wolf. The film came out at a time when teenagers and their tribulations were a trendy topic in cinema--Rebel Without a Cause was released two years beforehand—and using the werewolf curse as an analogy for the unsettling transformations of adolescence was the perfect way to update the long-dormant subgenre. But despite its rock-solid premise, I Was a Teenage Werewolf doesn’t quite hold together, its biggest mistake being its decision to let Tony drift into the background. Where Universal’s werewolves had back-and-forth transformations to get the most out of their anguish, Tony spends the latter half of the film as a snarling brute, with the (admittedly effective) exception of a scene in which he drifts around a lonely sunlit street like James Dean. With the teenage protagonist out of centre stage, attention instead falls on the grown-ups of Rockdale—the same characters who have been established as out-of-touch squares. No horror film has ever managed to get the audience on the side of the torch-wielding mob, but I Was a Teenage Werewolf appears not to have realised this. Moreover, the film appears strangely unaware of its own subtext. It closes with a surviving character making a portentous statement about mankind interfering with the affairs of God, as though it had been a meddling-with-nature story, rather than a clash-of-generations narrative. Although I Was a Teenage Werewolf never quite comprehended the full potential of its premise, other films took note. Tony’s lycanthropic antics were followed by a spate of teenage-oriented horror movies, from the semi-sequel I Was a Teenage Frankenstein through to the teen slashers that flourished in the eighties. The combination of monsters and adolescence had shown itself to be marketable—and a werewolf film was slap-bang at the start of the zeitgeist. At long last, werewolves were back. By Doris V. Sutherland Enjoy Doris' writing? Leave her a tip here through Ko-fi!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed