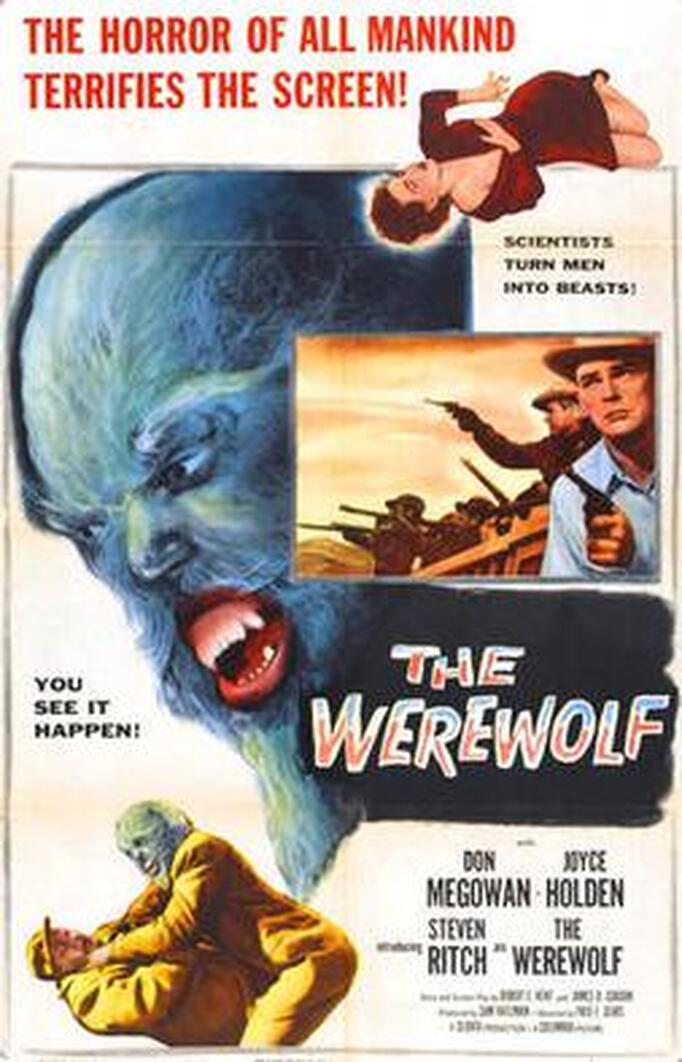

Welcome to a weekly series in which Doris V. Sutherland takes readers on a trip through the history of werewolf cinema... In The Werewolf (1956), A nervous man (Steven Ritch) walks into a bar at night and is followed out by one of the other patrons. The second man tries to mug him in an alleyway—but it turns out the would-be robber picked the wrong target. The outwardly meek man is a werewolf and transforms into a deadly beast when provoked. Before long, the locals—led by Sheriff Haines (Don Megowan)—are on a hunt for the killer. But can they track him down when they’re struggling to even accept the fact that a werewolf is loose in this small American town? Directed by Fred F. Sears with a script by Robert E. Kent and James B. Gordon, The Werewolf marked the end of a long hiatus for werewolf cinema. For context, the last time that Hollywood had made a full-on lycanthrope film—with no rational explanations, and without relegating the werewolf to a member of an ensemble—was Cry of the Werewolf back in 1944, a full twelve years beforehand. Moreover, the film was produced at a time in which horror cinema as a whole was in a state of flux. The Universal horror cycle was well and truly dead, with even the Abbott and Costello parodies having concluded in 1955, while Hammer’s full-colour, full-blooded Gothic revival would not begin until Curse of Frankenstein in 1957. The old monsters of horror films were having something of an identity crisis, and signs of this are all over The Werewolf. The film opens with a voiceover discussing werewolf folklore around the world, while a stray figure walks down a neon-lit night-time street straight out of a noir drama; all of this must have looked quite modern to audiences of 1956, and a world away from the misty forests and graveyards of Universal. The noir stylings continue through the sequence in which the werewolf kills the bar patron; indeed, as we don’t actually see him transform and the attack is conveyed in large part through shadows, the scene could easily have come from a fifties crime film. While past werewolf films typically showed the main character’s descent into lycanthropy or else staged themselves as whodunits, with the identity of the man beneath the fur saved for a twist revelation, The Werewolf comes up with a novel variation. We know from the start which character is the werewolf—but we know nothing of his history or how he became a werewolf. Not even the man himself is aware of his backstory, an amnesiac who can’t remember his own name, let alone how he ended up turning into a wolf-man. A short way into the film we learn that the werewolf’s affliction was caused by Dr. Morgan Chambers (George Lynn), who used him as the test subject for research into—of all things—the effects of nuclear war: “The human race will destroy itself not quickly but slowly. This wolf-man is the proof: radiation creates mutants, people who become monsters no longer human. They’ll make the hydrogen bomb more powerful and more powerful again, enough to change everyone on the Earth into a crawling inhuman thing through fallout radiation.” This plot element is not entirely new: The Mad Monster, produced during World War II, had George Zucco’s mad scientist scheming to create an army of invincible wolf men. But by updating this motive for the Cold War, The Werewolf takes on a different, more overtly apocalyptic tone. A fear of impending doom seems to permeate the film and can even be seen—albeit unintentionally—in the acting. The cast are proficient during the early stretches, when the culprit appears to be a garden-variety murderer, but freeze into total rigidity when trying to play characters confronted with a real, live werewolf. As a result, almost everyone in the film—save for the anguished lycanthrope—appears to be drifting around in a shell-shocked daze. A generous viewer might find value in The Werewolf as a film that takes the grimness and fatalism of lycanthrope subgenre—which had traditionally dealt with innocents being cursed through sheer bad luck and then marching steadily towards destruction—and updates these themes for the age of nuclear anxiety. But even the most generous viewer would be hard pressed to call the result anything other than dull. While the film certainly shows an earnest faith in its emotional core, with the sorrow of the werewolf’s wife and son a major plot point come the final act, the interminable sequences of small-town militias traipsing through woodlands looking for the fugitive wolf-man soon outstay their welcome. With its meek lycanthrope and flat leads, what The Werewolf really needed was a strong villain: an unabashed bad guy to chew the scenery, twirl his moustache and inject some actual life into the proceedings. Alas, Dr. Chambers turns out to be possibly the single most boring mad scientist in b-movie history, and for most of his screen time he and his assistant become just two more stiff faces in the crowd. All in all, The Werewolf was not the triumphant return for cinema lycanthropy that it should have been. But it can be seen as a dry run for a more successful release from the following year—when a certain teenage werewolf arrived in town. By Doris V. Sutherland Enjoy Doris' writing? Leave her a tip here through Ko-fi!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed