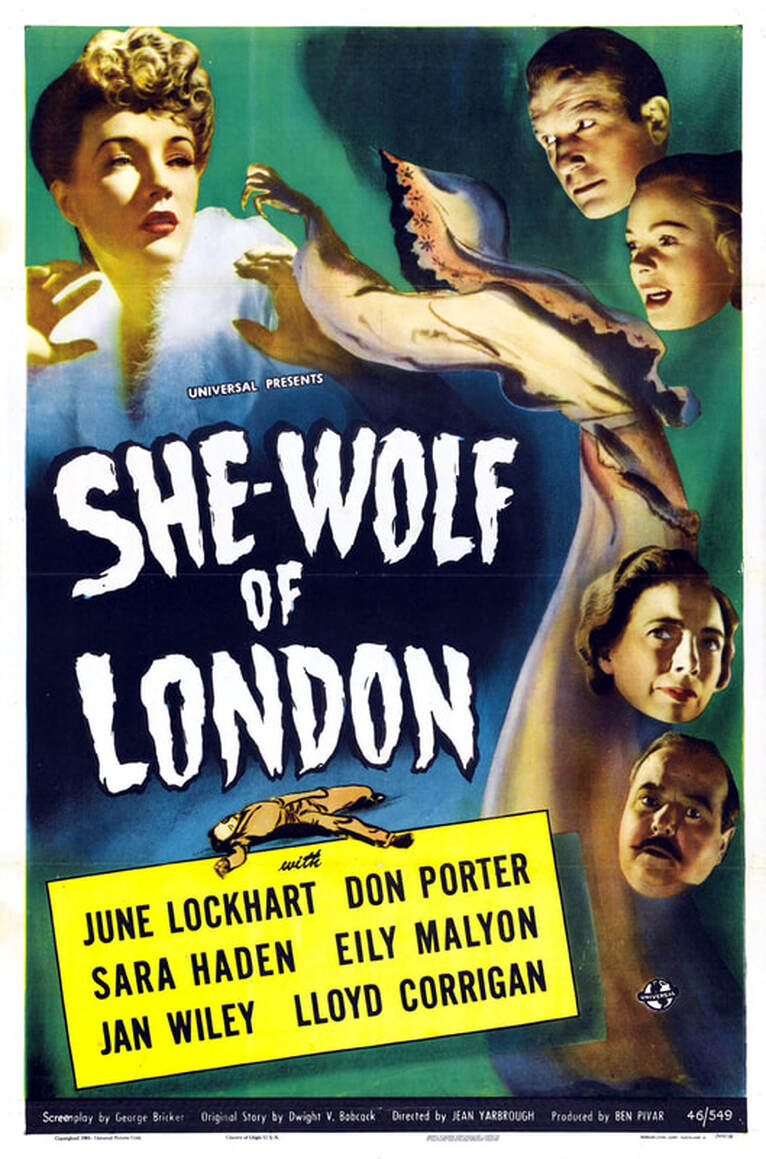

Welcome to a weekly series in which Doris V. Sutherland takes readers on a trip through the history of werewolf cinema... ...In She-Wolf of London (1946), Phyllis Allenby (June Lockhart) lives with her aunt Martha (Sara Haden), cousin Carol (Jan Wiley), and housekeeper Hannah (Eily Malyon). She is in love with Barry (Don Porter), but fears that should she marry him, she risks spreading the legendary Allenby Curse: the affliction of lycanthropy. Aunt Martha dismisses this as mere superstition, but when gruesome deaths begin occurring in the local park, it appears that the Allenby Curse is all too real. WARNING: SPOILERS AHEAD Directed by Jean Yarbrough from a script by George Bricker, She-Wolf of London is something of an oddity in the Universal werewolf cycle. Its title implies that it’s a sequel to Werewolf of London from 1935, a film that had long since been overshadowed by the more successful Wolf Man series with Lon Chaney Jr. But if anything it turns out to be even more of a throwback, taking place in a turn-of-the-century setting (something that must have felt cosily nostalgic to an audience that had just lived through World War II) and telling a story that seems to come from a world in which Universal’s full-blooded Gothic horrors never happened, and the gentler spook-melodramas of silent Hollywood held sway. One of the film’s unusual traits is its focus on women. Universal had tried female monsters in Dracula’s Daughter and Bride of Frankenstein, while rivals Columbia depicted a lady lycanthrope in Cry of the Werewolf, but each of these films followed the common convention of using only two prominent female characters – one good, one bad. But She-Wolf of London takes place in a household comprised of four women, and aside from various mostly interchangeable policemen, the only substantial male character is Barry, the Prince charming to Phyllis’ Cinderella. So, when the film establishes early on that the werewolf is female, this does little to narrow down the list of suspects. A short while afterwards Phyllis wakes up with bloodied hands and muddied shoes, seemingly confirming that she is the lycanthrope. Yet, there are signs that not all is as it seems: why, for one, is the face of the wolf-woman hidden whenever she goes out to kill? She-Wolf of London is another entry in the subgenre of werewolf whodunits, a combination established by The Undying Monster. Then, eventually, we come to the surprise revelation. The twist is that none of the characters are werewolves. Phyllis is actually the centre of an elaborate gaslighting campaign, using the legend of the Allenby curse to disrupt her romance with Barry; the real killer is not supernatural, merely unhinged. This plot point has obvious knock-on effects across the whole of the film. For one, it means that there can be no transformation sequences or even clear death scenes – hitherto the stock-in-trade of werewolf films. The horrors it portrays are therefore psychological, rather than visceral. She-Wolf of London was possibly influenced by Cat People, the 1942 classic that played on the ambiguity as to whether its protagonist was really a shapeshifting panther-woman or simply deluded. But the difference is that Cat People created an atmosphere of such taut paranoia that, at the end of the day, it didn’t matter if the woman’s condition was literal or symbolic: neither interpretation lessens the film’s effectiveness. If She-Wolf of London was attempting something similar then it clearly missed the point, as the story’s literal-minded conclusion leaves little room for symbolism. But still, the film does a remarkably good job within the confines of its limited premise. Yes, parts of it don’t stand up to close inspection – the plot depends heavily on the utter incompetence of the police force, for one – but it has enough good points to obscure its weaknesses. In particular, the dialogue and characterisation are far more naturalistic than is typically the case for a Gothic melodrama, with a high point being the scene in which Barry tries to have a level-headed conversation with Phyllis about werewolf folklore – only for her to break down in tears. Whatever its virtues, She-Wolf of London did little for werewolf cinema. Indeed, it marked the end of the 1940s werewolf boom. The period from 1941 to 1946 saw at least one werewolf film a year released onto screens; but after that came a dry spell. Aside from the Wolf Man joining the comedy ensemble of Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein in 1948, it would be a full decade before Hollywood mounted another lycanthropic picture with The Werewolf in 1956. By Doris V. Sutherland Enjoy Doris' writing? Leave her a tip here through Ko-fi!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed